UF researchers develop highly accurate 30-second COVID test

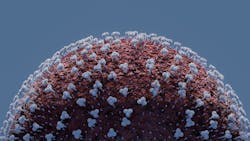

Researchers at the University of Florida have helped developed a COVID-19 testing device that can detect coronavirus infection in as little as 30 seconds as sensitively and accurately as a PCR, or polymerase chain reaction test, the gold standard of testing. They are working with scientists at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University in Taiwan.

At-home test kits offer results in minutes but are far less accurate or sensitive. The new device, researchers said, could transform public health officials’ ability to quickly detect and respond to the coronavirus — or the next pandemic.

UF has entered into a licensing agreement with a New Jersey company, Houndstoothe Analytics, in hopes of ultimately manufacturing and selling the device, not just to medical professionals but also to consumers.

Like PCR tests, the device is 90% accurate, researchers said, with the same sensitivity, according to a recent peer-reviewed study published by the UF group.

The device is not yet approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. First, researchers said, they have to ensure that test results are not thrown off by cross-contamination with other pathogens that might be found in the mouth and saliva. These include other coronaviruses, staph infections, the flu, pneumonia and 20 others. That work is ongoing.

The hand-held apparatus is powered by a 9-volt battery and uses an inexpensive test strip, similar to those used in blood glucose meters, with coronavirus antibodies attached to a gold-plated film at its tip. The strip is placed on the tongue to collect a tiny saliva sample.

The strip is then inserted into a reader connected to a circuit board with the brains of the device.

If someone is infected, the coronavirus in the saliva binds with the antibodies and begins a dance of sorts as they are prodded by two electrical pulses processed by a special transistor. A higher concentration of coronavirus changes the electrical conductance of the sample. That, in turn, alters the voltage of the electrical pulses.

The voltage signal is amplified a million times and converted to a numerical value — in a sense, the sample’s electrochemical fingerprint. That value will indicate a positive or negative result, and the lower the value, the higher the viral load. The device’s ability to quantify viral and antibody load makes it especially useful for clinical purposes, researchers said.

The product can be constructed for less than $50, Esquivel-Upshaw said. In contrast, PCR test equipment can cost thousands.