New Study Shows Substantial Species Barrier Preventing Transmission of Chronic Wasting Disease from Cervids to Humans

A new study, from National Institutes of Health scientists and published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, demonstrates that there is a “substantial species barrier preventing transmission of chronic wasting disease (CWD) from cervids—deer, elk and moose—to people.”

CWD is “a type of prion disease found in cervids, which are popular game animals.” It has never been found in people, but because of the mad cow disease outbreak in the United Kingdom in the 1980s and 1990s, which eventually killed 178 people, researchers have often wondered if it is transmissible to humans. CWD is “the most transmissible of the prion disease family, showing highly efficient transmission between cervids.”

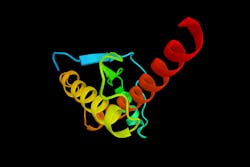

In 2019, NIAID scientists were able to create a “human cerebral organoid model” in order to study potential treatments for Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, which is what presented in the humans who died after eating meat infected with mad cow disease. Human cerebral organoids are “small spheres of human brain cells ranging in size from a poppy seed to a pea. Scientists grow organoids in dishes from human skin cells. The organization, structure, and electrical signaling of cerebral organoids are similar to brain tissue.”

The research team “exposed healthy human cerebral organoids for seven days with high concentrations of CWD prions” from cervids. Over six months, none of the organoids became infected with CWD. This indicates that “even following direct exposure of human central nervous system tissues to CWD prions there is a substantial resistance or barrier to the propagation of infection, according to researchers.”