NIH study highlights need to monitor prescription stimulant misuse

Researchers have identified a strong association between prevalence of prescription stimulant therapy for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and rates of prescription stimulant misuse (taken in a way other than as directed by a clinician) by students in middle and high schools. The study, which appears in JAMA Network Open, highlights the need for assessments and education in schools and communities to prevent medication-sharing among teens. This is especially important considering non-medical use of prescription stimulants among teens remains more prevalent than misuse of any other prescription drug, including opioids and benzodiazepines.

Supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the study used data collected between 2005 and 2020 by the Monitoring the Future (MTF). MTF is a large, multicohort survey of legal and illicit drug use among American adolescents in eighth, 10th, and 12th grade, also funded by NIDA.

“The drug supply has rapidly changed, and what looks like medications – bought online or shared among friends or family members – can contain fentanyl or other potent illicit substances that can result in overdoses. It’s important to raise awareness of these new risks for teens,” said NIDA Director Nora Volkow, M.D. “It’s also essential to provide the necessary resources and education to prevent misuse and support teens during this critical period in their lives when they encounter unique experiences and new stressors.”

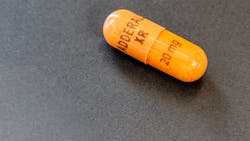

Stimulant therapy is an evidence-based treatment for ADHD, but it can also be harmful if used without prescription or guidance from clinicians. Prolonged stimulant misuse can lead to several detrimental health effects including cardiovascular conditions, depressed mood, overdoses, psychosis, anxiety, seizures, and stimulant use disorder.

Previous studies have shown that more than half of adolescents who misuse prescription stimulants get the medication for free from friends or relatives. While diagnoses of ADHD and prescribing of stimulant therapy for ADHD have increased significantly in the United States over the past 20 years, few studies have looked at the relationship between stimulant therapy and prescription stimulant misuse in schools. This is the first large, national study to examine prevalence of prescription stimulant misuse and factors correlating with prevalence among students in eighth, 10th, and 12th grade across the U.S.

Researchers at the University of Michigan examined both school- and individual-level characteristics associated with prescription stimulant misuse. Across 231,141 student participants surveyed at 3,284 secondary schools, the school-level prevalence of nonmedical use varied from 0% to over 25% of students. Schools with a greater number of students (12% or higher) reporting prescription stimulant therapy for ADHD tended to have the highest percentages of their student body reporting prescription stimulant misuse (8% of total student body). By comparison, schools with fewer students (0 to 6% of student body) reporting stimulant therapy for ADHD were associated with lower rates of prescription stimulant misuse (4 to 5% of student body).

Other features of schools that were associated with increased rates of misuse included having a higher proportion of parents with higher levels of education, being located in non-Northeastern regions and in suburban areas, having a higher proportion of non-Hispanic white students, and showing “medium-level” (10-19% of total student body) binge drinking. However, the association between school prevalence of stimulant therapy for ADHD and prescription stimulant misuse remained strong when accounting for prevalence of other types of substance use and numerous other individual- and school-level sociodemographics.

Recent research from this team expands on the associations found in this study, including a study that suggested teens with a history of taking both stimulant or non-stimulant medications for ADHD are at high risk for prescription stimulant misuse, as well as cocaine and methamphetamine use. The researchers note that it is important to interpret these results as associations, not causations, and that the primary goal of these kinds of studies is to inform effective preventative and support strategies for teens. The key takeaway here is not that we need to lessen prescribing of stimulants for students who need them, but that we need better ways to store, monitor, and screen for stimulant access and use among youth to prevent misuse,” said study author Sean Esteban McCabe, Ph.D. “There’s variation in stimulant misuse across different schools, so it’s important to assess schools and implement personalized interventions that work best for each school. It’s also critical to treat and educate teens on prescription stimulants as the medications they are intended to be and limit their availability as drugs of misuse.”