As pandemic ebbs, payday more than just a tasty candy bar in tough times

Even as the pandemic-addled supply chain endures pelts of media and public criticism for backlogs, shortages and universal inconvenience to spiraling popular demand, compensation levels for healthcare supply chain professionals seems to offer a much-needed respite from the pressure and tension.

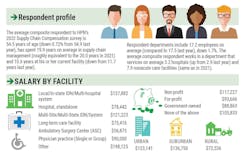

For the third consecutive year, the average salary for a Director/Manager of Materials Management/Supply Chain exceeded the six-figure ceiling, according to the results of Healthcare Purchasing News’ 2022 Supply Chain Compensation Survey.

Department leaders reported an average annual salary of $110,185, a 4.3% gain above 2021’s average of $105,693, which nearly matched the 4.5% increase over 2020’s statistic. The growth trajectory seems to be slowing since 2019, but it remains growth, the surveys have shown during the last three years.

Other titles within healthcare supply chain’s leadership reported solid, respectable gains as well. At or near the top, Executive/Senior/Corporate Vice Presidents saw their salary levels jump 12% on average to $204,629 from $182,794 the year before. Compensation growth for Purchasing Directors/Managers recorded tempering growth, edging up only 1.2% to $75,588 on average from $74,659, itself a 3.9% bump from the 2020 level of $71,875.

Overall, those survey respondents who received a compensation increase said it amounted to 3.6%, up from 3.2% last year.

Compensation levels for O.R. Materials Managers/Business Managers, increased 1.8% to $67,678 from $66,500 on average last year, while Senior Buyers/Buyers/Purchasing Agents saw their levels slide 2.6% to $49,285 from $50,592. Two other key titles saw significant drop-offs year-over-year on average – Chief Procurement/Purchasing/Supply Chain Officer and Value Analysis Director/Manager/Coordinator – but HPN explains the double-digit percentage decreases as due in part to lower sample sizes from those respondents checking the appropriate title boxes. Anecdotally, however, HPN also knows of several top-tier title holders earning in the high six-figure-to-low-seven-figure range, none of whom participated in this year’s survey. See the chart below for the survey tally.

One curious but notable result involves the areas where survey respondents indicated they directly manage inventory. The big year-to-year movers are found in the clinical and nonacute areas. Diagnostic imaging centers and hospital-based radiology departments saw the largest number of respondents and growth. Thirty-three percent of survey respondents said they service diagnostic imaging centers, 14.9% higher than last year; 40.8% said they service radiology departments, 9.3% higher than 2021. Supply Chain providing inventory services to the laboratory grew 5% with 30.6% of respondents involved. Finally, 21.4% of Supply Chain respondents indicated they provide inventory management services to physician practices, 2.9% higher than last year, according to survey results.

Although not illustrated this year, the overall supply chain management compensation composite index (something of an unscientific salary stew of results derived by the average aggregate salary of all survey respondents) finally poked through the six-digit milestone a year ahead of HPN predictions in 2021, surging 14.1% to $110,400 from $96,750, the all-time high last year. Historically, since 2005, HPN has recorded 11 CCI increases. This element, while more trivial than statistically significant, measures more of a subjective impression of attitude and direction.

As an ongoing cautionary caveat, HPN advises readers that survey data and trending perspectives hinges on a variety of demographic elements that include the number and mix of respondents by job title, facility type and location and gender. For example, more senior-level executives who lead centralized integrated delivery network (IDN) operations generally will elevate salary data, while more buyers at community hospitals may push the salary data lower.

HPN regularly monitors five key trending areas as illustrated in the charts and graphs within this annual feature.

In a stylistic departure from previous years, motivated by a desire for survey respondents to speak freely about their interpretation of the results and to share their raw observations about key issues and trends affecting the profession, HPN reached out to a variety of supply chain professionals, the majority of which are survey respondents, for their thoughts. To protect each from repercussions in a politically charged and sensitive culture, HPN granted each one anonymity, identifying only by gender, title and region of the nation in which his or her hospital, healthcare system or integrated delivery network (IDN) operates.

Gender studies

Men continue to earn more than women across the board. Check the charts here. The gap between them periodically has narrowed and widened since HPN began conducting this survey several decades ago. One year the survey saw women overtake men, and HPN thought a barrier had been broken … until a closer look at the survey demographics showed more women responding that year than men.

Not surprisingly, the survey results elicited few to no surprises from supply chain pros.

Per the male senior-level IDN Supply Chain Executive in the Southeast:

“I heard an interesting story on NPR the other day,” he said. “It was talking to the differences in the continuing gender pay gap, across different industries. The place with the highest gap was financial institutions. In many places Supply Chain still reports up through the CFO. Coincidence? Finance, in general, is a conservative, and for a long-time, male-dominated profession. In my experience, the finance industry is slow to adopt change and likes the status quo. Not everyone is that way, of course, but for many in the industry, this is true. So that may be part of the problem. Having said that, I am seeing more female CFOs and financial executives, so change may be coming.

“In the transition from Director of Materials Management to VP of Supply Chain, there were a group of cutting-edge leaders who demonstrated and created a path to executive leadership,” he continued. “At that time, I think there was more of a focus on getting a seat at the table, even though you may be the lowest compensated executive at that table. I think that was true for both men and woman in the early days. I think any raise seemed like recognition. The next generation looked at these existing executive positions and started pushing for pay equal to the other executives at the table. The new generation will accept nothing less than equal pay for the CIO, CNO, etc. As for gender, I do think we will finally see, in this next generation, a group of leaders who will be more focused on who can do the job and what is fair compensation for that job, regardless of their race, religion or pronouns.”

Per the female Supply Chain Director in the Southeast:

“Men have historically dominated the Materials Management/Supply Chain industry,” she said. “Healthcare Supply chain is no different. Healthcare organizations understand the value of the position that supply chain leadership can have, not necessarily based on gender. Women are still under-represented in healthcare leadership roles. However, as companies are aware of this and willing to make changes necessary, time will tell if women can once again overtake or come equal to men in their roles. Encouraging young women into the field of Supply Chain and Logistics, along with mentoring women who may just be entering into healthcare, will increase the female workforce in supply chain. Having strong female leadership in the C-suites as CEOs, CFOs and COOs can go a long way to help narrow the wage gap between men and women.”

Per the male Supply Chain Director in the Southeast:

“First, I believe that pay should be equal,” he said. “However, I believe that there are more men in Supply Chain leadership roles than women – at least from what I notice at national meetings with my peers. A lot of first starts for Supply Chain leaders is associated with laborious jobs. Warehousing, receiving and distribution, driving equipment, delivering products and equipment, lifting, etc. This may contribute to why women may not carry the same value as a male counterpart that has experience in the basic jobs listed. The women that I have known that have had success in Supply Chain were pretty tough ladies.”

Per the female Supply Chain Director in the West:

“Before we can compare, we need to confirm that the duties performed under a specific title are the same,” she observed. “I have worked for many different systems, under the same title, with different pay scales, and never had the same responsibilities. Also, each system may value each title a bit differently, as in my current role as Director, which is evaluated as a VP level.”

Per the female Value Analysis Director in the Northeast:

“Pay equity is a slow process that may take up to 268 years to close and is influenced by many factors,” she quipped. “There is no one magic fix to a decade’s long workplace practice. A holistic reason to close the pay gap is related to the U.S. poverty rate as quoted from Leanin.org: ‘Closing the pay gap isn’t just a win for women – it has social and economic benefits, too. If women were paid fairly, we could cut the poverty rate in half and inject over $500 billion into the U.S. economy.’ (https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/C455.pdf) The same article pointed out that this is not just a U.S. issue, but a global issue.

“The COVID years may have to some extent played a role in perpetuating the gap,” she continued. “Working from home may not have been perceived as ‘working’ or working less or working differently. Roles in the home, if perceived as inequitable where ‘housework,’ cooking, dishes, laundry, childcare may be taken on by women, may put more stress on leaving the workforce and shift the balance even more toward men potentially skewing the results.”

Age, Experience and Longevity

The trend seems to be the more experience you gain, which can take years, and/or the longer you stay within an organization, which can generate influence and power, then the more you tend to earn.

Observed the female Supply Chain Director in the Southeast:

“It is rare these days to find leaders under the age of 40 who stay in one position for more than 7-10 years,” she noted. “This has been the norm for seasoned supply chain professionals, yet unless there is a clear path and timeline for advancement, it is time to move on. Learn as much as you can and take that knowledge and experience and use it elsewhere. If you are able to relocate and work in nonacute care or long-term care and continue to grow in supply chain field, then I think you are more valuable than staying in one position for many years. Anyone looking at the résumé will see this person takes risks, enjoys change and is not stuck in one company’s thought processes.”

Observed the male Supply Chain Director in the Southeast:

“Experience is key,” he noted. “Healthcare supply chain experience in large part is a result of mentorship,” he noted. “Only recently in the past decade or so have colleges even taught supply chain-related courses. However, not only mentorship, but also the individual has to be very conceptual in order to understand the cause and effect of the healthcare supply chain. I think that both moving from place to place or staying with an organization for a long period can elevate a person. However, it is the person that can gain trust and can be an influencer with others that elevates in this profession. I started my career at an organization that I was at for a long time. However, when I left and applied for a position as a Director versus the title of Corporate Manager, I had to meet with and influence C-suite level managers to gain their trust in order to win that role. I think that a successful person can elevate in either situation.”

Observed the female Supply Chain Director in the West:

“The trend I have experienced in my 25-plus years in Supply Chain is that if you stay within a system, you are only going to grow with the small annual increase, even if you get a new title,” she noted. “The current system no longer sees the value. One must move around to advance/elevate your title and increase your compensation, as the new system sees your value.”

Observed the female Value Analysis Director in the Northeast:

“It's not a matter of making sense to moving around but doing so out of necessity based on the how the current system ‘works,’” she noted. “Moving around can be the product of following a significant other for opportunity to advance with/without salary improvement, educational opportunities, transfer within systems spanning multiple regions, etc. Much depends on lifestyle, priorities, availability, ‘right time-right place-right fit’ and what you are willing to settle for.”

Observed the male senior-level IDN Supply Chain Executive in the Southeast:

“I think this is so very organization specific,” he noted. “Having said that, if you stay at the same place you will see increased compensation, year over year. But I think that in order to see significant change in title or compensation, you have to be able to really market your achievements internally and be seen as a true asset to the organization. If the organization is progressive, it may recognize your true value. Even then, the organization may heap praise but not money on you. So you may need take your talents [elsewhere] if the current organization is not willing to compensate you in the way the open market will. I would find it hard to believe that in the majority of cases, significant compensation [change] came without changing organizations.

“I don’t have a magic number, but I have noticed that the average number of years, with no career movement for this up-and-coming generation, seems to be between three and five years,” he continued. “I will say that if I look at a résumé and there are several, two-to-three-year positions, that is a red flag for me. However, it seems like job hopping is becoming more acceptable with this generation. There is also a much stronger core value that they have to believe in what they are doing and where they work. However, I also think there is, in some cases, a real lack of appreciation for what they don’t know. Way too much focus on advancement, without achievement and little focus leadership development.”

Education, Training and Certification

The trend seems to be the higher education you receive – including degrees and learning new skills and thinking – the higher your income trajectory. But how does or should educational advancement – including certification – really contribute to the direction of compensation levels against the backdrop of a demanding post-pandemic world?

Noted the male Supply Chain Director in the Southeast:

“I believe that in every profession education/certification levels affect earnings,” he indicated. “More and more a Master’s degree is the norm. Bachelor’s degrees are more like a GED. Especially advancement to a Director-level or VP requires that the candidate has higher levels of education. It also is the norm to have a certification in Supply Chain (CMRP or CSCP, etc.). Problem solving, sourcing, critical thinking, communication with all levels of management, use of professional connections all contributed to being successful during the pandemic. Also, those attributes can be related to the personal abilities that an individual needs to accomplish with higher levels of education.”

Noted the female Supply Chain Director in the West:

“It’s only when you move from system to system does the value of additional education provide influence,” she indicated. “The current systems will encourage educational advancement, perhaps even pay you to do so. However, the final result will not guarantee increased compensation or promotion.”

Noted the female Value Analysis Director in the Northeast:

“Because of the last two years it should be more obvious that Supply Chain requires levels of expertise through the chain,” she indicated. “From Master’s prepared business administration to Bachelor’s/certified project managers, from data analysts for new KPIs armed with ability to take disparate information and produce proactive signaling to LEAN-certified performance improvement facilitators to technology-savvy high school-trade school-community college-armed services-trained inventory, warehouse and distribution managers with supply chain experience.

“The carrot should be well-written job/role/career ladders that entice and encourage individuals with the above qualifications to take supply chain seriously as a profession. Along with the ladder comes compensation rewards for your personal improvement that will lead to organizational improvement.”

Noted the male senior-level IDN Supply Chain Executive in the Southeast:

“I think that the industry as a whole needs to reevaluate the obsession with higher education,” he indicated. “In part because so many [human resources] application systems are set to automatically filter on the qualifications of the job description. In the past you may list the need for a degree, but you would get all of the résumés and you could weigh experience and skills against the need for a degree. You could talk to a variety of candidates with different backgrounds. In this way, you could match a person and their skills and characteristics to an organization’s needs and its culture.

“I am afraid what is happening more and more often is matching a job description to a CV on paper. Résumés for excellent and experienced candidates may never make it to a leader’s desk because of the bias toward a degree. A good part of many jobs, including Supply Chain, is [on-the-job training], and I think that is proving out more and more. Confident and strategic supply chain leaders managed the pandemic well, regardless of their degree status. On the other hand, leaders that looked good on paper were quickly overwhelmed.

“Requirements for degrees and certifications can be a self-fulfilling prophecy,” he continued. “‘I got one, so you have to get one to work for me or my organization’ is the wrong reason to put degree and certificate requirements in a job description. I think everyone is a product of how they came up in their careers, and depending on your experience or background, a degree may or may not add to your ability to do the job. As for certifications, they usually involve a test of some kind that everyone studies for and when they pass, they get the ‘certificate.’ How much they retain and how much they ever apply in their real jobs is questionable. Between degrees and certificates, I would say I value certain degrees more and most certificates less. Association memberships and certificates can just become money grabs, and the saddest part is that folks in most need of additional education, networking and leadership development, can least afford the fees and costs associated with membership.”

Noted the female Supply Chain Director in the Southeast:

“Education is valued and required in supply chain without a doubt,” she indicated. “However, that has not always been the case. There are successful supply chain leaders who have risen in their careers – myself included – through hands-on learning and experience. Continuing to accept new obstacles, ask questions, and grow in the job will lead to advancement.

“Yes, the certification programs and higher education can help,” she continued, “but I think experience plays a larger role. Prior to 2020, supply chain was rarely spoken. The last two years of facing the daily shortages, backorders, and other challenges within healthcare have brought new awareness to the industry. You can have a Master’s degree and still not know how to handle a crisis as we have been through. To be sure, there are great skills that can be taught in higher education, but then again, the task-oriented and relationship skills are usually obtained through experience.”

Hospital type, regional location

The trend seems to be that the higher-compensated Supply Chain executives and professionals seem to entrench themselves at larger urban not-for-profit hospitals, followed by investor-owned facilities and then suburban not-for-profit hospitals with government facilities bringing up the rear. How might the pandemic-driven focus on nonacute, remote care and telehealth affected that pattern going forward?

Said the female Supply Chain Director in the West:

“This is interesting,” she indicated. “With Value-Based Purchasing, we shall see those Executives/Professionals take on the role working on Supply Chain initiatives from inside the four walls of the hospital to out in the community – supply diversity focused. Thus, the roles/titles will become enterprise-oriented with compensation levels increasing.”

Said the female Value Analysis Director in the Northeast:

“Rather than looking at it from the employee view, let’s look at it from the employer point of view,” she indicated. “To attract professionals to an urban area with a high cost of living, traffic, crowding and other conditions the compensation matches the need. As you work out from the concentric circles to other work/life areas it does not mean the compensation should be different. Look at it from the [point of view] of the level of care your healthcare organization is providing to your community. Employers need to attract candidates from the same pool as the urban ring to provide the same good outcomes and keep thriving. If we have learned nothing but one thing, we have learned Supply Chain is key to the health system ecosystems survival.”

Said the female Supply Chain Director in the Southeast:

“The larger urban-type environments usually have the top-named healthcare organizations,” she indicated. “The smaller rural areas can face challenges in recruitment of qualified supply chain executives and tend to have more ‘home-grown’ options. With so many changes in hospital organizations with mergers and acquisitions, it is tough to decide which area is the right fit. Nonacute care can be very competitive in the job market, and many people overlook this area. Hospice and Continuing Care Retirement Communities have an important role prior to acute care. Telemedicine had a major advancement in 2020 thanks to COVID as many organizations were in the early discovery phase of this option and then moved quickly to make it happen. Finding new ways to care for patients has become the priority. Mobile clinics, satellite clinics and telemedicine can help hospitals in all demographics care for their patients on a wider basis.”

Said the male Supply Chain Director in the Southeast:

“My opinion is that not-for-profit organizations have more dependency on their Supply Chain professionals,” he indicated. “There is probably less depth in supply chain leadership, so higher dependency. “For-profit organizations have centralized corporate supply chain offices that staff higher- level and more leaders in one place. This may be why off-site managers make less salaries because they are more operational versus the centralized leaders. Therefore, in a large organization, higher salaries are centralized and lower salaries are decentralized.

“Nonacute care and telehealth is not a new trend,” he clarified. “Our organization has been moving toward building and opening smaller offsite locations as outpatient procedures are increasing. This is occurring for many reasons (space constraints, etc.), but the biggest reason is changes in reimbursements associated with alternate care sites.”

Lasting pandemic effects

For the third consecutive year, the average annual salary for Supply Chain leaders at the director level has exceeded the $100,000 threshold. Granted, this partially can be attributed to cost-of-living concerns and the geographic location and organization type of the respondent. Further, most respondents said they feel rather secure in their positions. The pandemic certainly emphasized the need for – and value of – the supply chain and value analysis functions during a time of crisis and heightened demand for products and services. But as the pandemic subsides, is the profession seasoned enough to succeed in the future?

Indicated the female Value Analysis Director in the Northeast:

“The culture of each healthcare system was challenged by the pandemic,” she said. “Some of those cultures were overwhelmed and some thrived. The ‘COVID Era’ has set the stage for high-demand information sharing, virtual networking, transparency, exchange of practices, a proverbial potpourri of ‘how are you handling that.’ Supply Chain leaders, arm-and-arm with their executives, must look inward and take stock of their foundational operations and human/physical/technology resources to reset their strategies, goals and tactics to meet the future path their organizations must take in the new, emerging healthcare swirling around them.”

Indicated the male senior-level IDN Supply Chain Executive in the Southeast:

“It is likely that supply chains that did well managing the past several years of ongoing supply chain issues, worked well with clinicians and leaders on how to handle backorders and helped to manage cost well, are feeling very safe in their organizations and their roles. Their CEOs likely have a new respect for the importance of a high-functioning Supply Chain. These same CEOs are likely more willing to compensate their Supply Chain teams more competitively to keep their level of confidence in a successful team. Unfortunately, I know of more than one example, through peer-to-peer discussions, of a lack of appreciation, such as Monday-morning quarterbacking by senior executives [asking], ‘Why did we have to buy all that stuff and why did it have to be so expensive?’”

Indicated the female Supply Chain Director in the Southeast:

“Over the years as supply expenses continued to rise and the reimbursement has declined, the value in a qualified supply chain leader has never been more important,” she said. “With that, value should come the higher compensation. Every product line is being looked at to see where money can be saved, yet still having the best possible product and outcomes. Supply Chain is not just placing product orders; we are looking at sourcing, reimbursement, standardization, quality and value of products. Working with Group Purchasing Organizations (GPO) to obtain better pricing with aggregate spending that smaller facilities might not be able to take advantage of on their own, and reviewing contracts to ensure correct pricing are just two actions that can reduce spending. Organizations that provide a seat at the table for Supply Chain executives understand the value of what we do each day. The respect and appreciation should have been there before the crisis/disaster occurred, but we tend to be in the background as a service department for the clinical areas. Having the day-to-day understanding of caring for the patients, yet being fiscally responsible to the organization, is what we do every day. This is the future of supply chain.”

Indicated the male Supply Chain Director in the Southeast:

“It’s funny,” he said, “I have never met so much and so often with senior leadership than when the pandemic started. I sat with my CEO one very late afternoon and told him that I was the president of the state’s chapter of Supply Chain professionals and that my job was to get recognition for Supply Chain professionals, then kiddingly said, ‘but not like this!’ Meaning that I did not want to be put in the position that I was in reacting to the challenges that developed because of the pandemic. I think that Supply Chain professionals are extremely appreciated at this time, and I hope that – like me – they have been financially recognized.

“I have always been at the top of the salary compensation level,” he continued. “Most Supply Chain professionals report to CFOs who are usually stingy with money. Early in my career I passed on my first job offer as a Supply Chain manager. The offer was given by the Human Resources department. When the CFO called me and asked why I turned it down, I told him that it was the salary offer. After negotiating an acceptable salary, the CFO stated, ‘I would have been disappointed if you hadn’t negotiated out of the gate for your own salary. I know that I have the right guy.’ I would expect my colleagues to do the same. Unfortunately, the data from the salary surveys does not support that.

“I think that the future for Supply Chain professionals is bright post-pandemic. Now with all of the Supply Chain logistics-related issues, Supply Chain professionals are even more important. It did take the pandemic to kick this in the butt. Whenever I see my CEO or COO, they are always happy to see me and ask questions related to the challenges that we have with all of the global issues affecting deliveries. I do believe that compensation should trend higher.”

Indicated the female Supply Chain Director in the West:

“Supply Chain and Value Analysis are definitely in the spotlight more than ever,” she said. “The pandemic brought the Supply chain out of the basement and to the Boardroom, enhancing the value that the hard work these teams have provided to staff and patient safety. I also see how the current Supply Chain shortage affects the nation that everyone is hearing in the news, social media and in their local communities. With the mandates for vaccination, many resources are leaving the healthcare market and/or deciding to retire. The nation is seeing this backlash as the available resources to replace the workforce is limited. With the continued stress on the Supply Chain, burnout is a real issue – administrators need to take notice on how to address before there is a crisis with lack of resources.”

About the Author

Rick Dana Barlow

Senior Editor

Rick Dana Barlow is Senior Editor for Healthcare Purchasing News, an Endeavor Business Media publication. He can be reached at [email protected].