One of the keys to success for an effective and safe surgical procedure is having the necessary instruments and supplies in the room for the surgeon and operating room (OR) team before the patient arrives. While on the surface this might seem like a simple concept, getting the right products into the right surgeon’s hand at the right time requires a complex alignment of people, processes and information behind the scenes.

When a surgeon is missing an item, or has been given the wrong item, it can result in case delays and potentially patient harm. On the other hand, when staff members pick and deliver to the OR items that go unused, it adds time, labor and costs as soft supplies are returned to inventory and the central sterile/sterile processing department (CS/SPD) processes instruments that never touched the patient.

Procedural kit/tray planning can include some common challenges, but CS/SPD professionals, Supply Chain leaders and supplier executives share potential solutions to improve accuracy, efficiency and safety.

Physician preference problem

Because they are the ones performing the procedures, it makes sense that the surgeons would dictate which products they use in the OR. But in a facility where numerous surgeons are requesting a wide range of suppliers and technologies based on their individual preferences, the procurement, processing, storage and management of these items can wreak havoc on supply chain, CS/SPD and OR staff alike.

When physician preference alone drives tray and kit planning, a facility finds itself with various configurations for the same procedure, each based on an individual surgeon’s needs. This level of variation not only increases cost for the organization and more work for those involved in managing these items (supply chain, CS/SPD and OR), but also increases the risk for error, particularly when it comes to picking and assembling supplies.

“Hospital protocol for surgical procedures can vary across facilities—as can tray preferences for surgeons within the same facility—leading to multiple surgical procedure tray configurations, in some cases for the same procedure,” said Gary Rabinovich, Marketing Director, Procedural Kits & Trays, Halyard Global Products Division of Owens & Minor. “Carrying these redundant configurations creates inventory management inefficiencies and waste when protocols and preferences evolve.”

Get organized

“SPD is a dynamic workplace with many moving parts,” said Hendee. “The staff must focus and have great attention to detail to properly inspect and package instruments. Organizing and standardizing the layout of instrument trays and providing staff with easy-to-follow set lists will greatly improve effective and efficient inspection. This, coupled with selecting the appropriate tray itself, will ensure they are stocked adequately and allow more focus on the important job of inspection.

“The same is true for procedures and requirements to properly sterilize and store instruments,” Hendee added. “Giving thought to what is stored where (by service for instance) and making sure staff members are organized while placing items into sterile storage will greatly impact how easily and efficiently they can be removed for use.”

Collaborate for change

Because the actions of the CS/SPD impact the OR, and vice versa, neither department can work in a silo as they address kit/tray planning challenges. Stakeholders from both teams must come together in a collaborative way to develop a solution that meets the needs of both departments.

Lane explains how her department works very closely with OR clinical leaders, providing feedback to one another in real time to prevent “hiccups” in their day-to-day operations.

“At our daily huddles, we discuss in detail the concerns we may have with the next day’s operating room schedule and, when possible, we rearrange the schedule,” said Lane. “When that is not possible, we set up a plan to ensure the OR provides the CS/SPD trays requiring immediate turnover prior to the room being cleaned so we are able to expedite their reprocessing per the manufacturer’s instructions for use (IFU). Having a good working relationship with the clinical leaders and the leaders in CS/SPD is critical to our daily operations, but when we are facing challenges associated with tray turnover, it requires us to be extra vigilant and very clear in our communications in order to prevent any delays.”

Rabinovich says collaboration among the OR, supply chain and a healthcare organization’s suppliers can help drive supply standardization, stating:

“Supply chain and OR clinical staff need to regularly collaborate and review existing surgical trays with their supplier to identify opportunities for standardization. This can help reduce costs for the standardized, higher-volume procedure trays while also reducing inventory and obsolescence costs.

“Facilities should also consider surgical suture kits for complex procedures requiring a large number of sutures,” Rabinovich added. “Using kits where sutures are pre-opened and arranged in the correct order can reduce the time typically required to gather, open and arrange supplies.”

While most OR, CS/SPD and supply chain teams recognize that supply variation can negatively impact costs, workflow and patient care, many do not have accurate and complete data on product usage by surgeon and procedure to present a case for change.

Matt Bruggeman, Sr. Director, Presource Products & Services, Cardinal Health, stresses this need for a data-driven approach to procedural supply management, describing how it can help healthcare organizations maximize the value of their resources and spend.

“Effectively calibrating procedural supply spend and clinical utilization can be challenging, namely due to variation in products procured, pulled and used in surgical procedures,” said Bruggeman. “Analytics can help spur necessary conversation between CS/SPD and OR staff by objectively presenting data and sparking dialog to prompt action. The output of these conversations can impact how a procedural supply chain is managed, driving new efficiencies and cost savings. For instance, thoughtfully reducing variation, using common products and kit componentry, enables providers to decrease SKU count, reduce inventory on the shelf, minimize waste and, most importantly, provide more time for patient care. This will be even more important as facilities continue to resume surgeries following the COVID-19 pandemic.”

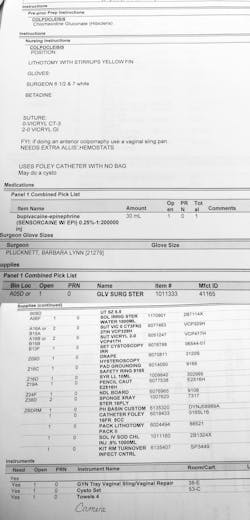

Physician preference cards: The recipe for success

In reality, healthcare organizations struggle to maintain preference card accuracy. The items that a surgeon specified for a procedure in the past may not be the same items he or she require today. As an organization negotiates new contracts and supply purchases, and brings new items into its facilities, OR staff members must revisit preference cards with surgeons, but other priorities, most notably direct patient care, tend to get in the way. As surgeons leave a facility, and new ones join, the OR team must update their systems to reflect the preferences of these new surgeons, while removing those that are now obsolete. In some cases, the OR team continues to add items to a physician’s preference card as they request new instruments and other supplies, but never deletes those no longer in use.

The CS/SPD team at Geisinger Community Medical Center (CMC) experienced the pain of inaccurate physician preference cards first hand, according to the hospital’s Sterile Processing Manager Manny Rodriguez.

To address the issue, Rodriguez and his team first looked at which products hadn’t been used in the past three years and made a list of those items segmented by surgical specialty (e.g. orthopedics, general surgery, ENT). They met with the OR manager, surgical services director and pod coordinators for the ORs to review the list. The pod coordinators took their designated lists and met with their teams to decide what they should keep or discard and where they could lower par levels for items they were not frequently used. Rodriguez’s team reconvened with the OR team to create a general list of items to keep, discard or adjust and made changes accordingly.

To maintain physician preference card accuracy moving forward, CMC hired an individual solely responsible for correcting preference cards on a real-time basis. The OR keeps the empty packaging for supplies used in a case and the individual updates the preference card based on what the surgeon actually used, versus what he or she requested.

“I’m sure this project will save my staff members time and, if they are picking cases faster, I can reallocate their time to other projects,” said Rodriguez.

Another organization that has addressed the challenges around physician preference cards is Mercy. The health system’s perioperative team collaborated with Tecsys on a perpetual inventory management system in which clinical, operational and financial workflows are driven by preference cards.

About the Author

Kara Nadeau

Senior Contributing Editor

Kara Nadeau is Sterile Processing Editor for Healthcare Purchasing News.