Future care: There’s no place like home

Meet Donna, a 42-year-old dental hygienist who lives in Portland, OR with her family of three children and husband. She recently received bad news: Her mother, who lives near Los Angeles, has fallen ill, and Donna needs to see her as soon as possible.

Donna immediately begins her internet search for a good pilot. Her local airport has links to airlines and a “Find a Pilot” link, so it seems straight forward, but Donna hasn’t flown for years, as she usually prefers driving to California. Donna is in a hurry, so she picks the one with the highest “star-reviews.” Unfortunately, that pilot is not taking new passengers. The next highest rated pilot isn’t available for three months.

Donna knows flying is risky; she just read recently that one in every 100 flights has a safety issue. She looks at the next five pilots’ profiles, but their safety records are not public, so she needs to take a guess based on years of experience and the schools they attended. She picks one named Jane, who has a flight available in two days, and quickly reserves a seat.

Soon after, Donna receives an email from the airline giving her instructions on how to prepare for the flight and payment options. Fortunately, her family has good transportation insurance, so most of her travel costs will be covered, but she still needs to pay a sizeable portion of the aircraft fuel to meet her deductible. Donna calls the insurance company to make sure she is preauthorized for the flight.

The day before the flight, the airport sends Donna an email with instructions on how to get to the airport, where to park, and how to get to the gate. Some of the procedures conflict with the instructions from the airline, so Donna calls the airline to clarify them.

The airport is preparing for the flight, as per its usual protocols. The airport pulls the preference card for Pilot Jane and makes sure the ground crew and flight attendants are informed of her specific requests. Pilot Jane, with a typical East Coast training, likes to use a short runway and demands the northern takeoff approach, so the airport makes the necessary adjustments in the flight schedule.

Donna finds her seat on the plane, and feeling a bit nervous, she asks the passenger seated next to her, “Hi, have you ever flown with Pilot Jane before?” The elderly man replies, “Oh yes, I’ve flown with her several times. She’s a little slow, but I do like her better than the pilot she replaced who retired a few years ago.”

It’s a month later, and Donna has been back home for about two weeks. She receives several pieces of mail related to the trip, including a bill from the airport, another from the airline, and something from the insurance company. Fortunately, she is familiar with dental office billings, so she is able to sift through the paperwork and figure out how much she owes out of pocket to which party. She is surprised that the airline charged for two packets of sugar for her coffee, when she never even used sugar, and the airport charged a fee for parking when she already paid on the way out. She also received another bill that she thought was junk mail but turned out to be an invoice from the vendor who runs the motorized jetways; she never even knew that was an outsourced service.

Not surprisingly, this tale is an allegory that may seem familiar. In fact, if you replace “pilot” with “surgeon,” “airport” with “hospital,” “airline” with “clinic,” and other analogous terms, you might recognize a very typical experience for almost every person who has undergone a clinical/medical/ surgical procedure in the United States.

From air care to healthcare

Comparisons between the airline industries and healthcare systems have been made for years, and many articles and books have been written on the topic. The premise is that both industries involve highly regulated services where consumers are literally putting their lives in the hands of trained professionals. Both require the practice of high reliability to reduce errors with a focus on safety, which over many years, the airline industry has been able to achieve within Six Sigma standards. However, one key difference is that the airline industry achieved a very high level of safety while developing a consumer-centered business model.

Sad to say, the healthcare industry has achieved neither the same level of safety nor a consumer (patient) centric model of service.

What could a patient-centered model look like for a perioperative experience?

Patient-centricism

Meet Todd, a 58-year-old man recently diagnosed with a tumor in his colon. His doctor referred him to a surgeon who recommended surgery. Now Todd must navigate through how to get this done.

The surgeon’s office gives him a referral to the local perioperative clinic. Before Todd gets home, he already receives a text from the clinic. The text includes a link to a scheduling site that allows him to pick an appointment date within the next three days. Todd enters initial information through the secure site and receives instructions for his appointment. At the appointment, he meets a perioperative medicine clinician who goes through his entire medical history and standardized, evidence-based risk assessment tools. Todd receives a customized plan and is assigned a personal navigator.

Todd is assured that an appropriate preoperative optimization will maximize his chances of a good experience without affecting his chances of a cure. In fact, standardized preoperative optimization of his overall health will improve his risk of complications and his chances of a good surgical outcome. At the clinic, he undergoes standardized programs for smoking cessation, treatment for anemia, and prehabilitation to increase his exercise tolerance. A personal navigator reviews Todd’s progress and helps him schedule the surgery within the following six weeks, giving enough time for him to get physically and mentally prepared as well as get his life in order for the post-operative period.

The clinic communicates the plan seamlessly to the hospital through a common electronic health record system, and all information is readily accessible to Todd via his patient portal. All costs related to the surgery are listed clearly, including Todd’s share, based on his health plan. There will be no surprise billings, and later, after the perioperative experience is over, he will receive all results and invoices via his portal.

As Todd prepares for his surgery, he receives a single set of instructions from the clinic so that there is no confusion. He arrives at the hospital as instructed, and there are no glitches – no missing paperwork, no missed labs, no conflicting instructions that were not followed. Safety checks are performed using standardized checklists. All staff is focused on the comfort and safety of the patient. The operating room feels welcoming with all staff working as a team to focus on the patient experience. The anesthesia professional, whom Todd met earlier, follows standard enhanced recovery protocols (ERP) to ensure all safety risks are double-checked.

Todd recovers from surgery predictably without problems and is discharged home in three days without the need for prescription pain medications, thanks to the ERP. The clinic remains the primary resource for the next three months to make sure Todd follows up with the right doctors and addresses any postoperative issues.

Homeward unbound

Todd’s experience may seem too good to be true, but some hospital organizations have already begun implementing these concepts. One such concept is known as the Perioperative Surgical Home (PSH).

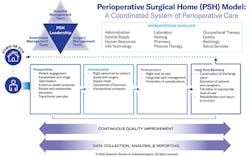

According to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), the PSH is “a system for organizing and coordinating care that is patient-centered, physician-led and team-based. PSH care extends from the decision for surgery until completion of recovery.” Much work has been done in the past years to demonstrate that implementing PSH protocols result in improvements in:

- Quality of care

- Patient safety and medical errors

- Opioid use

- Hospital length of stay

- Readmissions and returns to the emergency department

- Postoperative complications, both medical and surgical

- Total cost of care

- Patient satisfaction

- Provider satisfaction

- Hospital revenue

- Reduction of waste and unnecessary variation

Establishing a PSH includes giving the patient the sense of a “home” for all surgical needs, which could be in the form of a physical clinic or virtual platform. Even more critical, however, is the coordinated multidisciplinary team that is led by a clinician who is responsible for overseeing perioperative medical care. While not yet a formally designated specialty, Perioperative Medicine is fast becoming recognized as a much-needed practice that encompasses the care of the whole person centered around a procedural episode.

Common barriers that hospital organizations encounter when attempting to establish a PSH include:

- Lack of financial modeling

- Lack of leadership

- Lack of care coordination resources

- Information technology challenges

- Cultural resistance against change or standardization

- Lack of clinical champions

- Competing interests between specialties

None of these barriers are insurmountable, and in fact, much can be gained by implementing even a small piece of the PSH (e.g., a single specialty ERP) to begin with, and small successes will often catalyze rapid expansion of the program. A nationwide PSH Learning Collaborative of the ASA was able to demonstrate that an initial investment into a well-supported PSH program uniformly resulted in strong clinical and/or financial returns.

Providence, a 51-hospital integrated delivery network (IDN) in seven western states, adopted the PSH as the best-practice model for optimizing the patient experience. One major regional medical center saw significant improvements just six months after implementation, including a reduction in length of stay to 4.1 days from 4.9, readmissions to 9.9 percent from 12.4 percent, reoperations to zero from 2.1 percent and patient-controlled opioid use to 18.7 percent from 24.7 percent.

Dramatic improvements in patient satisfaction were demonstrated by improvements in Press-Ganey scores and consistent patient feedback. For example, scores improved for “speed of discharge” to 92.3 from 52.4, for “overall care” to 92.3 from 81.8, and for “likely to recommend” to 92.3 from 76.2. Based on these and other successes, a maturity model was developed as a template for guiding other hospitals to achieve high-level patient experiences and outcomes using evidence-based tools.

Healthcare is undergoing rapid changes as it tries to keep up with consumerism trends and demands for digital solutions. The COVID-19 pandemic has added even greater urgency to these changes, and as healthcare provider organizations struggle to identify more opportunities to innovate, the PSH is an ideal example of a patient-centered model of optimizing cost, quality and outcomes.

About the Author

Jimmy Chung, M.D.

Jimmy Chung, M.D., MBA, FACS, FABQAURP, CMRP, is Chief Medical Officer, Advantus Health Partners, a subsidiary of Bon Secours Mercy Health, Cincinnati. Chung is a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Healthcare Purchasing News, and next month becomes Chair, Association for Healthcare Resource & Materials Management (AHRMM) Advisory Board.