Narrating the pathogenesis of a deep organ surgical infection

When dead, sterile bioburden gets deposited into the body from a contaminated instrument during a surgical procedure, the foreign, organic material begins to decompose and is attacked by phagocytes. Phagocytes are the white blood cells that protect the body from harm by ingesting (phagocytosing) harmful foreign particles, including dead, sterile, organic cells. Part of this process involves the production of lysozymes that break down the cell walls of the dead, sterile, organic material. Frequently, those cell walls contain endotoxins that are then released into the blood stream.

As the body tries to fight the dead, sterile, organic bioburden with a rapid increase in the production of lysozymes, you also see an increase in body temperature due to the infection caused by the release of the bacterial toxins. This process is frequently seen in surgical patients who present with a fever of unknown origin and an elevated white blood cell count within 24- 48 hours of surgery.

The real danger caused by the release of endotoxins from the dead, sterile, organic cells is the body’s response to the endotoxins. Once detected in the bloodstream, endotoxins stimulate cytokine production. The rapid production of cytokines can trigger the systemic inflammatory response syndrome that can potentially cause multiple system organ failure. An intra-abdominal infection following abdominal surgery is one of the most common causes of multiple system organ failure.

If dead, sterile bioburden gets deposited into the body of a patient whose immune system is suppressed or compromised, the consequences can be much more severe. If bacterial toxins are released into the bloodstream of a patient whose immune system cannot rapidly produce white blood cells, septic shock is a possible consequence of the bacterial toxins in the bloodstream.

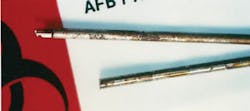

For examples, see the five photos here. Please understand that these are photographs of “non-take-apart” reusable instruments that were disassembled after being reprocessed. The Kerrisons were disassembled for sharpening by an instrument repair technician. Had they not been sent out for sharpening, they would have been used on the next patient!

The same is true of the photos of the laparoscopic instruments. I disassembled them during some of my research into bioburden and instruments years ago. Regretfully, nothing has changed in the ensuing years.

Please note that the residual bioburden inside of these instruments is not the fault of SPD personnel. The fault resides with the poor design of the instruments (internal square shoulders, long channels, multiple corners and internal dead spaces that collect and trap bioburden). During the normal opening and closing of these instruments during a case, some of that trapped bioburden can fall out of the instrument and cause an infection.

Given the inherent design flaws in these instruments, they can be difficult, if not impossible, to thoroughly decontaminate and clean during the reprocessing cycle, even if being reprocessed by extremely dedicated personnel. In the absence of validated IFUs to prove that instruments can be thoroughly decontaminated, cleaned and sterilized, you will continue to see instruments like these being returned to surgery on a daily basis and infecting innocent patients.

About the Author