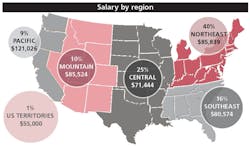

Healthcare Purchasing News’ 2018 Infection Prevention Salary Survey revealed good news this year. The average salary jumped by almost $6,000, to $84,296 this year, compared to 2017’s $78,345. The 2018 median salary is $82,500, a leap of $10,000 over 2017.

Raises in 2018 are very similar to 2017’s numbers. This year, 61 percent of respondents received a raise, slightly better than the 60 percent in 2017; 33 percent’s salary remained the same, compared to 35 percent in 2017; 6 percent experienced a decrease in salary in both 2017 and 2018.

News on bonuses is much like 2017’s, too. This year, 73 percent do not expect a bonus, which is a little less than last year’s 78 percent. Both in 2017 and 2018, 13 percent expected a bonus. In 2018, 14 percent don’t know if they will receive a bonus, compared to 9 percent in 2017. Among those who expect to receive a bonus, the percentage of which is based on their current salary, 53 percent of respondents anticipate a 1 to 2 percent bonus, 31 percent expect a 3 to 4 percent bonus, 6 percent expect a 5 to 6 percent bonus, with the remaining 9 percent of respondents expecting a bonus of 7 percent or more.

Becky O’Connor, RN, BSN, CIC, Infection Control, St. Vincent Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, offered valid reasons as to why those charged with hiring staff at healthcare facilities should look closely at salaries and bonuses as a means of attracting and retaining experienced infection preventionists (IPs). “Healthcare should evaluate the IP salaries with an eye on recruitment and retention. There are companies that provide infection-prevention services, such as the National Healthcare Safety Network, for facilities at a premium price. Hospital systems have had to avail themselves of those services when the infection-prevention positions are open.

“This is a niche area,” continued O’Connor, “as experienced IPs are not abundant, and they can affect the bottom line of healthcare facilities. It also takes many months to develop an IP with the minimal competency to practice, least of all become certified in this specialty.” All are sound reasons for offering financial incentives for IPs to stay in place.

Job security news is both better and worse. Last year, 48 percent felt very secure, whereas, in 2018, 50 percent feel very secure, a slight upswing. In 2017, 47 percent felt somewhat secure, but only 39 percent feel somewhat secure this year. Last year, 5 percent felt somewhat insecure, but that number unfortunately doubled to 11 percent this year.

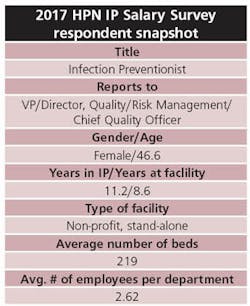

The information gathered from the survey is based on 218 respondents, similar to last year’s number at 220. This year’s composite IP is female, and she is almost 46 years old, one year younger than 2017’s composite. She is a registered nurse (RN), certified by the Certification Board of Infection Control and Epidemiology, Inc (CBIC), and her title is infection preventionist. She reports to the VP/Dir, Quality/Risk Management or Chief Quality Officer. She has been in infection prevention an average of 12 years and has worked at her current facility for 9 years. She is employed at a nonprofit, standalone facility with 227 beds. There are 3 employees in her department. These numbers are almost identical to last year’s snapshot.

Our respondents are primarily female (92 percent); 6 percent are male, and 2 percent declined to answer this question.

The majority (79 percent) of our respondents are RNs, as usual. Educators and medical technologists comprise 14 percent each. The remaining 22 percent include epidemiologists; licensed vocational nurses, licensed practical nurses, or nurse practitioners; laboratory technicians; physicians; and legal nurses.

Most often, our respondents report directly to the VP/Dir, Quality/Risk Management or Chief Quality Officer, 42 percent; chief nursing officer, 17 percent; and director or manager of infection prevention, 17 percent.

Nine percent of respondents have worked in infection prevention for less than 2 years; 17 percent, 2 to 4 years; 19 percent, 5 to 9 years; 19 percent, 10 to 14 years; 13 percent, 15 to 19 years; 13 percent, 20 to 24 years; and 9 percent have worked in infection prevention more than 25 years.

Seventeen percent of respondents have worked in infection prevention less than 2 years at the facility at which they are currently employed. Twenty-five percent have worked there between 2 and 4 years; 22 percent between 5 and 9 years; 17 percent, 10 to 14 years; 7 percent, 15 to 19 years; 6 percent, 20 to 24 years; and 6 percent have worked more than 25 years at their current facility.

There is not much improvement in facilities’ being in line with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations of one IP per 100 beds, 46 percent this year versus 45 percent last year. Twenty-six percent of respondents report their facility is not in line with CDC recommendations. It is puzzling that 28 percent do not have a clue as to whether their facility meets the CDC ratio of 1:100.

Diana Sargent, RN, ICP, Laurel Ridge Treatment Center, San Antonio, TX, talked further about demands on the IP. “More important than all the number data is the role of the ICP. Infection control has advanced dramatically regarding the amount of training they need to have, the information they are required to know, their role in patient care, and the reporting and evaluating needs of their place of employment. This training and knowledge is utilized to help the IP with safe patient care and employees with safe patient-care practices. It looks at all facets of infection control.”

In O’Connor’s view, “Infection preventionists are required to be responsible for increasing areas of responsibility, both from an inpatient and outpatient perspective. It is not uncommon for an IP to have responsibility for some or all of the inpatient units as well as designated outpatient areas. In addition, the facility IPs also bear a great deal of responsibility from a regulatory standpoint regarding nonclinical areas such as dietary, facilities, construction, supply chain, and volunteer services. It can take a great deal of work to get nondirect patient-care staff to recognize and value their importance regarding infection prevention.”

O’Connor’s concern also relates to the survey question, “Do you feel the C-suite at your facility appreciates and understands the IP’s role in providing good patient care while managing costs?” Fifty percent of respondents answered yes, they do, a small decrease compared to 53 percent in 2017. Thirty-six percent said no, they don’t see evidence of administrative understanding, which is a similar percentage to 2017. Fourteen percent, a rise of 2 percent over last year, have no idea if the C-suite appreciates the IP’s role in managing costs.

O’Connor added, “Because infection prevention is a ‘cost avoidance,’ versus a ‘revenue generator,’ it can be a struggle to obtain the resources needed to develop and maintain an effective infection-prevention program.”

As seen by Krieg’s, Sargent’s, and O’Connor’s observations, division of time among duties is a serious concern for most IPs. Our survey found that less than half of respondents, 44 percent, have the luxury of spending 100 percent of their time on infection prevention; however, that does represent small gain over 2017’s 36 percent. Twelve percent spend 90 to 99 percent of their time on infection prevention, compared to 7 percent last year, another small improvement; 11 percent, 80 to 89 percent; 8 percent, 70 to 79 percent; 7 percent, 60 to 69 percent; and 9 percent can spend only 50 to 59 percent of their time on infection prevention.

Show me the money

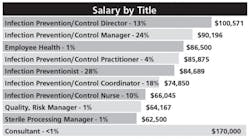

Breaking down the numbers by title and salary, infection preventionist is the most commonly mentioned title, 28 percent, with an average salary of $84,689, followed by infection prevention or control manager, 24 percent, at $90,196; infection-prevention or control coordinator, 18 percent, $74,850; infection-prevention or control director, 13 percent, $100,571; infection-prevention or control nurse, 10 percent, $66,045; infection-prevention or control practitioner, 4 percent, $85,875; sterile processing manager, 1 percent, $62,500; employee health, 1 percent, $86,500; and quality or risk manager, 1 percent, $64,167.

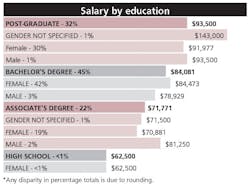

As for level of education versus salary, Sargent pointed out the data demonstrated, “The type of education that the IP has attained seems to have an impact on salary. Approximately 22 percent of the IPs hold an associate’s degree in nursing; 45 percent, a bachelor’s degree; and 32 percent of the population surveyed are postgraduate IPs. This indicates a large number of the IPs have a bachelor’s or higher degree. This ties into the salary area, because RNs with a bachelor’s or a higher degree tend to make higher salaries.”

Sargent’s statements regarding level of education being evident in salaries are borne out by the statistics gathered in the survey. More good news is that salaries in all categories of education rose this year. Salaries broken down by degree held by the respondents are as follows: postgraduates make an average of $93,500, up from $89,117 in 2017; bachelor’s degree, $84,081, compared to $76,545 last year; associate’s degree, $71,771, compared to $69,771 last year; and high-school graduates, $62,500, up from $60,000 last year.

Sargent noticed, “Out of the 218 IPs that were surveyed, 54 percent have their CIC from the Certification Board of Infection Control and Epidemiology, Inc. Again, this certification will have a direct impact on the ICPs’ salary.” The 36 percent of respondents who reported they have no certifications may find that observation important to their career as well as potential earnings.

Where she works

In 2018, most of our respondents, 69 percent, are employed at a nonprofit facility. Twenty-three percent work at a for-profit facility, 6 percent at a government-owned facility, and 2 percent work in other environments. Thirty-eight percent of the facilities are located in a rural setting, 32 percent in an urban setting, and 30 percent are in the suburbs. These numbers are very close to 2017’s.

The majority of respondents, 58 percent, are employed at a standalone hospital. Twenty-seven percent are employed at an integrated healthcare-delivery network, alliance, or multi-group health system. Six percent work at behavioral or psychiatric facilities. The remainder work in a variety of settings including surgical centers or ambulatory care, clinics, group practices, rehabilitation, and insurance.

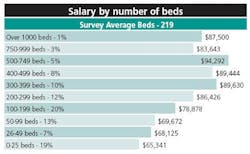

The size of facility in which our composite IP works averages 227 beds; however, most respondents still work in smaller facilities, with 73 percent employed at facilities with beds numbering between 0 and 299. Eighteen percent of respondents work in a facility with 0 to 25 beds; 6 percent, 24 to 49 beds; 10 percent, 50 to 99 beds; 22 percent, 100 to 199 beds; 17 percent, 200 to 299 beds; 11 percent, 300 to 399 beds; 6 percent, 400-499 beds; 6 percent, 500 to 749 beds; and 5 percent, 750-999 beds.

Issues, interests, and (yet more) responsibilities

Among the 63 percent who answered yes to participating in a product-evaluation committee, their role revolves around these areas: safety evaluation, 52 percent; determine need, 48 percent; product testing, 39 percent; process improvement, 36 percent; education, 30 percent; cost analysis, 27 percent; define usage, 21 percent; and other areas not listed, 4 percent.

The top ten areas for which our respondents are responsible for purchasing, specifying, or evaluating are hand sanitizers, 79 percent; disinfectants and sterilants, 77 percent; cleaning equipment and supplies, 68 percent; handwashing systems and hand-hygiene monitoring, 66 percent; masks and respirators, 57 percent; needlestick or sharps safety devices, 54 percent; gloves, 51 percent; protective wear, 48 percent; ATP cleaning verification or testing devices, 44 percent; and antimicrobial surfaces or coatings, 42 percent.

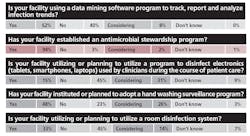

Forty-eight percent of respondents’ facilities either already have adopted, or are planning to adopt, a handwashing surveillance program. Oddly, the number dropped this year and last year. In 2017, 53 percent answered yes, and in 2016, 60 percent answered yes. Twenty-three percent do not have such a system, 26 percent are considering adopting a handwashing surveillance program, and 3 percent of respondents do not know what, if anything, is planned for their facility regarding handwashing surveillance.

In light of the many published scientific articles confirming that handwashing surveillance programs far outperform manual observation for accuracy, it is concerning that the numbers are dropping; however, that may change. Krieg offered an interesting observation on hand-hygiene surveillance. “I believe that next year’s survey will see an upswing in the number of facilities adopting a handwashing surveillance program, because The Joint Commission is now issuing tags for individual lapses in hand hygiene, instead of looking for a pattern of noncompliance as basis for a tag.”

In 2017, only 24 percent of respondents’ facilities reported using, or planning to use, a room-disinfection system. This year, that number jumped by almost 10 percent, to 33 percent. In 2017, 50 percent reported not using a room-disinfection system, and that number dropped a bit to 45 percent this year, which is a bit of good news. Fourteen percent of respondents’ facilities are considering a system, compared to 20 percent last year, and 7 percent don’t know, compared to 5 percent last year. Among those who reported using a room-disinfection system, the numbers are heavy on ultraviolet light, followed by hydrogen-peroxide fogging.

Antimicrobial resistance continues to blossom as a worldwide problem. Fortunately, it is now being taken seriously, and it shows in our numbers. Last year 85 percent of respondents said their facility had established an antimicrobial stewardship program. This year, the number is even better at 94 percent. Only 3 percent, 2 percent less than 2017, admitted their facility had not adopted a program; 2 percent are considering a program, compared to 9 percent last year; and 1 percent do not know, the same percentage as in 2016 and 2017.

Fortunately the number of those using data-mining software programs to track, report, and analyze infection trends increased again this year to 52 percent, up from 46 percent in 2017. Forty percent still are not making use of such programs, but that is a slight improvement over last year’s 49 percent. This year, 8 percent are considering using a data-mining software program, a little better than last year’s 5 percent.

Using data-mining software to manage infection data has the advantage of speed and accuracy, but it also frees up more of IPs’ time to spend on infection prevention that would have been used on laboriously and manually collecting, reporting, and disseminating the data. O’Connor offered good advice, “A robust surveillance system makes a great deal of difference regarding the identification, tracking, and prevention of hospital-acquired infections. All surveillance systems are definitely not created equally, and the infection-control staff must have input into a hospital system’s decision.”

Conclusion

Healthcare Purchasing News’ Infection Prevention Salary is your story, for you and by you. Participants’ responses reveal where you fit in the infection-prevention stream of things, for salary and so much more. Only IPs can interpret what the numbers collected mean to your professional life. Sharing your insights tells us which issues are important to IPs and why. Consider participating in this story for our 2019 Infection Prevention Salary Survey next year, as Krieg, Sargent, and O’Connor did this year. Your input and interpretation of what the numbers say add value to the information collected that only you, as an IP, can provide.

About the Author

Susan Cantrell

Susan Cantrell is Infection Prevention Editor for Healthcare Purchasing News.