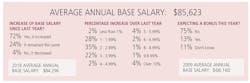

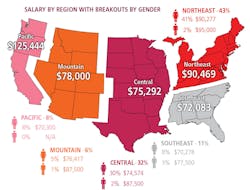

This year, the majority of infection preventionists (IP) reported an increase in base salary over last year (72 percent), with an average annual salary of $85,623 in 2019, compared with $84,296 in 2018. Most respondents (87 percent) reported that their pay raises were between 1 and 4 percent in 2019, with only 13 percent expecting a bonus this year, which is similar to previous years.

“I believe IPs should be compensated for what we prevent in terms of infections based on the numbers that we produce for a facility,” said Rodriguez. “This is evident because IPs are also educators providing guidance and feedback to staff in how to prevent HAIs, policy, protocols and so much more. We cannot prevent infections by just sitting behind a desk. We have to get out onto the units by rounding and communicating with staff.”

As noted, job security is high among the survey respondents, with 53 percent stating they feel “very secure” in their positions, and 42 percent “somewhat secure.”

“I think the profession is very secure. Many IPs started their careers in the 1980s when the role was new and are now getting ready to retire so facilities need to fill these positions. I’ve also found there is high demand for interim roles, so if you are willing to travel there are many job opportunities available.”

“It’s really a revolving door,” said Rodriguez. “The reasons behind this are varied. But some people enter the profession not understanding the challenges and realize they can’t weather the storm, whether it is the workload, salary or the ability to deal with different styles of personalities from nursing staff to leadership. I am however very fortunate to have a company as well as leadership who understands the importance of IP. You have to be a certain type of person to succeed in IP. You must be self-sufficient, self-motivated and know how to use your networking and resources to make a difference in whatever you’re trying to tackle.”

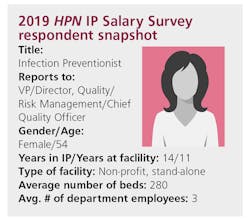

This year’s composite IP is female, and she is 54 years old, which is 3 years older than 2018’s composite. She is a registered nurse (RN), certified by the Certification Board of Infection Control and Epidemiology (CBIC), and her title is Infection Preventionist. She reports to the VP/Director, Quality/Risk Management or Chief Quality Officer. She has been in infection prevention an average of 14 years and has worked at her current facility for 11 years. She is employed at a nonprofit, standalone facility with 280 beds. There are 3 employees in her department.

Recognition

The percentage of respondents that believe the C-suite in their facilities appreciates and understands the IP role in providing good patient care while managing costs rose from 50 percent in 2018, to 55 percent in 2019. Rodriguez attributes this increased recognition to high-profile infectious disease outbreaks, and reimbursement tied to patient outcomes and patient satisfaction scores.

“The trends that have been happening lately in IP with acute care hospitals for instance, have really brought the infection prevention world to the forefront,” said Rodriguez. “I think what happened with Ebola really changed things for IP by highlighting the knowledge and background that we bring to the table to prevent HAIs.”

“This is an exciting time for us and I hope this is a trend for infection prevention overall,” said Donovan. “Historically, as infection control, we were in the background crunching numbers and giving updates. Now as infection preventionists, we have come more to the forefront. We are being brought into the mix earlier when leaders are making decisions, which I think is a good thing.”

Education and certification

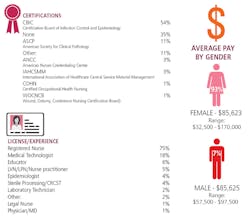

The majority of this year’s survey respondents hold Bachelor’s degrees (54 percent), followed by post-graduate degrees (24 percent), Associate’s degrees (20 percent), and high school diplomas (3 percent). As in previous years, IP salaries are closely tied to level of education, with those respondents holding post-graduate degrees earning the most at an average of $104,722 in 2019, and those with high school diplomas alone earning the least, at an average of $42,500 annually.

Rodriguez says that while in the past those with Masters in Public Health degrees tended to take positions in state offices or with government agencies, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more IPs working within health systems and hospitals are earning this degree.

“Also it seems the healthcare industry might be moving toward requiring IP professionals to hold Bachelor’s of Science in Nursing (BSN) degrees or an Associate’s degree in Nursing over diploma RNs,” Rodriguez added.1

Among this year’s survey respondents, 75 percent were registered nurses, while 18 percent were medical technologists. The same number of respondents as last year reported being certified by the CBIC and the American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP), at 54 percent and 11 percent respectively.

Donovan, who is the President of the Maine Chapter of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), says education has been a strategic focus for his chapter this year. They have placed an emphasis on IPs investing in both themselves, and in the future of the profession.

“We anticipate that in the next five years or so there will be a huge changeover as veteran IP practitioners retire and new IPs enter the field,” said Donovan. “We will need to get these new IPs up and running quickly because the work is so fast paced and changes so quickly.

“Certification and education for IPs are critical, but many facilities have trouble securing funds to support these activities,” Donovan added. “Purse strings are tight and there are so many competing priorities. One area that could be improved from a C-suite perspective is recognition that the profession is changing and that it is imperative that we continue to be given opportunities for ongoing education so that we can drive cutting-edge initiatives for infection prevention within our organizations.”

Cheryl Flesner, RN, BSN, CIC, Infection Preventionist, Dignity Health, Sequoia Hospital, in Redwood City, CA, notes how the California APIC Coordinating Council (CACC) has collaborated with the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) to advance IP education in the state.

“With the huge number of competencies that are needed, education of the IP is paramount,” said Flesner. “Yet, at times, IPs must pay for their own education because hospitals are on tight budgets and restrict education travel. Both the CACC and the CDPH have done a great job of trying to provide education for beginning IPs in our state, with CACC offering a new IP foundation class, and CDPH offering a two-day class for new IPs.”

Roles and responsibilities

“When people think IP they think of hand hygiene but we are much more than that,” said Rodriguez. “In this role you are not only a nurse but also an educator, a microbiologist, epidemiologist and your own leader. We have a lot to cover in terms of roles and responsibilities. My facility is an acute care hospital so from the rooftop down to the basement there is not one area in which IP doesn’t have a say.”

When asked what percent of work time is spent in infection prevention, 46 percent of survey respondents said 100 percent, with IPs spending the rest of their time on activities such as employee/occupational health (32 percent), National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) (25 percent), disaster/bioterrorism preparedness (18 percent), education/compliance (16 percent), immunization/vaccination (14 percent) and quality performance management (11 percent).

“Often in critical access hospitals the infection preventionists have additional responsibilities which sometimes include, employee health, clinical nurse educator, emergency preparedness, quality coordinator and others,” explained Harper. “They may have one additional or all. Since my background is in medical laboratory science, it’s not within my scope of practice to work in employee health or provide clinical nurse education.”

“It is a layer of the job that hadn’t been there before, or at least not in such a heavily scrutinized way,” said Donovan. “Some of these scores can impact quality data for an entire system depending on how the reporting is structured.”

The majority of IPs surveyed (33 percent) said they report directly to the VP/Director, Quality/Risk Management/Chief Quality Officer, followed by Chief Nursing Officer (CNO) (18 percent) and Director/Manager Infection Prevention (18 percent).

“Roles and responsibilities in IP are expanded exponentially,” said Flesner. “There is an intense focus in construction mitigation, emerging pathogens such as CRE and MDR-Pseudomonas and MDR-Acinetobacter, and Ebola, new mandatory reporting, pressure to reduce device-related HAIs including CLABSI and CAUTI, a new intense focus on high-level disinfection and sterile processing, and surgical site infection (SSI) reduction. The IP is in the center of all these prevention efforts.”

Collaboration

Rodriguez explains how IP collaboration with other departments and teams is critical to an effective infection prevention strategy, particularly nursing and environmental services (EVS). She notes that when she was an ICU nurse she was using product bundles intended to reduce ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP), CAUTI and central line associated blood stream infections (CLABSI), but nobody had explained exactly why they were doing this.

“When I took over the IP program, I took the education I had gained to the bedside nurses and said, ‘Did you know that if we don›t use this bundle then a patient could get this HAI and this is the percentage that can be withheld in terms of reimbursement? And not only that, we will get a bad report card in terms of HCAHPS, Leapfrog survey percentages and rankings.’ Nobody had explained it to them in that manner.”

As for EVS, Rodriguez says she works hand-in-hand with this team, calling them out as, “the number one reason why our infections are down.” She describes them as being her “eyes and ears on the unit,” adding:

“Nursing staff has their own niche with the bundles and hand hygiene, but EVS has a huge role to play. When protecting patients against infections on a unit, the first thing that needs to happen is that environmental services must complete a thorough and precise cleaning. As an IP, you must be in good communication with EVS to explain how important their job is and how they have a huge factor in helping us keep our infections down. I provide education to the EVS department throughout the year, and they in turn report to me on what nursing staff are/are not doing when it comes to IP protocols.”

Trends and technologies

In this year’s survey, as in past years, we questioned IPs on policies, programs and products they have in place to reduce the risk for infections. The vast majority of IPs (92 percent) surveyed said their facilities had established an antimicrobial stewardship program, with nearly half (49 percent) saying it had been effective in reducing infection rates.

Over half of those surveyed (54 percent) said their facilities are using a data mining software program to track, report and analyze infection trends, and nearly half (45 percent) said their facility instituted or planned to adopt a hand-washing surveillance program.

About one-third (32 percent) of respondents said their facility used or was planning to use a room disinfection system, While only 13 percent of respondents said their facility instituted or planned to adopt a program aimed at disinfecting electronics (tablets, smartphone, laptops) increasingly used by clinicians during the course of patient care; an additional 32 percent said they were considering such a program.

When asked if their facility’s IP-per-patient ratio aligned with current CDC recommendations (1:100), only 38 percent said “yes,” which is down from 46 percent last year.

Product evaluation and selection

With regards to products, 64 percent of respondents said they were members of their facilities’ Product Evaluation Committees. When asked what role they played on these committees, the highest response percentages were in product safety evaluation (47 percent) and determining the need for a product (47 percent).

“Infection preventionists are a resource and collaborate with every department in a hospital,” said Harper. “Often we provide consultation but should not be responsible for implementation of changes in each area, especially when it relates to product evaluation and selection.”Rodriguez said she has been approached by an increasing number of vendors asking for her approval/endorsement to pitch their products to the hospital. Her advice to vendors when approaching IP: Have your evidence in hand.

“A lot of companies out there that say they have the latest and greatest and try to bid for the IP’s approval/endorsement but they don’t have the studies or white papers to back their claims,” said Rodriguez. “For example, five years ago I looked at one product that sounded good but I told the vendor that I needed more detailed information. I revisited the same company and product last year and found they had detailed studies and white papers so I agreed to let them show us their product. Good communication from a company is a must for me if I am to consider bringing its product into my facility to impact HAIs.”

Note: All percentages were rounded to their nearest whole numbers.

References

1. Requirements for Initial Certification and for Lapsed Certificants, Certification Board of Infection Control and Epidemiology (CBIC) https://www.cbic.org/CBIC/Candidate-Handbook/Eligibility-Requirements.htm

About the Author

Kara Nadeau

Senior Contributing Editor

Kara Nadeau is Sterile Processing Editor for Healthcare Purchasing News.