MIT team collaborates with 3M to develop rapid COVID-19 low-cost diagnostic test

3M is collaborating with the Sikes Lab to jointly develop a COVID-19 diagnostic test, including establishing novel processes for scaling it, reports MIT News.

Hadley Sikes, an associate professor of chemical engineering at MIT, has been working for years with her team on the technology they’re adapting to create a COVID-19 test with rapid results. Moving beyond lab prototypes and into manufacturing the diagnostics on a large scale, however, is new territory.

“What amazes me about Hadley is her ability to use incredibly smart science to engineer a solution to a real-world problem, and take that solution all the way to translation at such a rapid pace, considering materials, cost analysis, and even manufacturing in true chemical engineering spirit,” says Paula Hammond, the David H. Koch Chair Professor of Engineering and head of the Department of Chemical Engineering. “Even as much of the world was forced to a halt, the Sikes Lab has never stopped innovating and was committed to refining their technology toward COVID-19 testing. We welcome this collaboration with 3M and what the partnership will make possible.”

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) selected the rapid COVID-19 test for accelerated development and commercialization support, after rigorous review by an expert panel. The test is in the Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics Tech (RADx Tech) program, an aggressively paced COVID-19 diagnostics initiative from the NIH’s National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering.

“We are excited to collaborate with Professor Hadley Sikes and the team at MIT. Our approach is ambitious, but our collective expertise can make a difference for people around the world, so we owe it to ourselves and society to give it our best effort,” says John Banovetz, 3M senior vice president for innovation and stewardship and chief technology officer. “This is another step demonstrating 3M’s leadership in the fight against COVID-19. We are seeking to improve the speed, accessibility, and affordability of testing for the virus, a major step in helping to prevent its spread.”

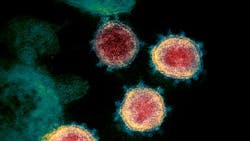

Sikes saw room to innovate in the field of coronavirus testing, as the RNA tests in widespread use can take days to get results from nasal swabs and have been difficult to scale in the United States. The rapid test being developed by the Sikes Lab and 3M is based on binding proteins and would be available at much lower cost.

“Ours is a test for the proteins of the virus rather than its genetic material, and you don’t need to send a sample to the lab for processing,” she says. “Our goal is that someone with minimal training could perform the test within minutes.” RNA tests being the norm has presented challenges and a bottleneck for the team, as biorepositories and reference specimens are still not set up for protein tests.

The work aimed at getting the test from lab to market has been unusual. MIT’s labs had closed in March along with the campus, but the Sikes Lab remained open on a limited basis with support from the Department of Chemical Engineering. Eric Miller, a postdoc who helped develop the technology while completing his PhD, spent long hours in the lab engineering reagents that capture and label SARS-CoV-2 proteins.

Reagents prepared at MIT were overnighted to Sikes’ lab in Singapore, where she is a principal investigator in the Antimicrobial Resistance Interdisciplinary Research Group (AMR IRG), co-led by professors Peter Preiser of Nanyang Technological University and Pete Dedon of MIT, at Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART). Lab members in SMART and at MIT worked together to build prototype tests and develop user-friendly procedures.

At MIT, the Deshpande Center for Technological Innovation, the Technology Licensing Office, and the Office of Strategic Transactions worked with Sikes to establish an agreement with 3M, bringing an understanding of the commercialization process with companies and “speaking their language,” she says.

Sikes’ tests had already been successful in detecting identified markers for malaria, tuberculosis, and dengue before the coronavirus outbreak. The binding proteins in her test attach to coronavirus proteins and enable detection by associating a color change with their presence. Conceptually, it is similar to an over-the-counter pregnancy test, though the format and components differ in ways that make it more scalable. The COVID-19 test would not need to be administered in a medical setting.

3M’s diverse technology and manufacturing capabilities were an ideal match for development and mass manufacturing of this new kind of paper-based diagnostic. The company produces 50 million N95 respirators a month in the US and has doubled global N95 respirator production globally. Pending validation of the test, the goal of the Sikes Lab, 3M, and RADx is to produce millions of the affordable, accurate tests each day in the US. With operations across the globe, 3M could eventually build up manufacturing capacity to supply tests around the world.

Sikes stressed the enormity of the team effort across organizations, which included 15 researchers in her labs, with others at SMART AMR IRG pitching in; more than 30 experts at 3M; about a dozen at NIH RADx; many staff members at MIT; and Deshpande Center “Catalyst” mentors and their networks in industry. This research is being funded by MIT’s Deshpande Center, SMART, and the NIH.

“It’s a rare collaboration of government, industry, and university to innovate at a rapid pace in this pandemic,” she says. “Our groups and many others across the globe are doing our best to rise to the daunting challenge of swiftly adapting and deploying new technologies to increase COVID-19 testing.”

Reprinted with permission of MIT News