The facts on monkeypox

According to a release by the Mayo Clinic Health System, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has indicated a U.S. resident tested positive for monkeypox after returning to the U.S. from Canada.

The CDC also is tracking multiple clusters of monkeypox cases that have been reported in early to mid-May in regions that don't normally report monkeypox, including Europe and North America.

What is monkeypox?

Monkeypox was first discovered in a colony of monkeys in 1958. The first human case of the virus was recorded in the Congo in 1970. Since then, it has mostly been reported in African countries.

Monkeypox is an infection from animals caused by a virus closely related to the smallpox virus. Infection is transmitted to humans through scratches or bites from infected animals, such as rodents or nonhuman primates, or eating bush meat.

Human-to-human transmission occurs through direct contact with skin lesions, bodily fluids or through large respiratory droplets. Transmission is limited to close household contacts or healthcare workers not wearing personal protective equipment.

"There has never been an outbreak of this size outside of Africa. We now have about 120 known or suspected cases across 12 different countries. This is unprecedented," says Gregory Poland, M.D., head of Mayo Clinic's Vaccine Research Group.

Monkeypox symptoms

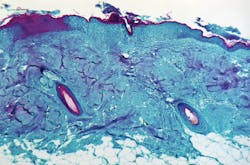

Initial symptoms are fever, headache and swollen lymph nodes. This is followed by a rash. The rash initially consists of flat patches. It then progresses to raised nodules and then to vesicles, with one to two days in each phase. The final stage of pus-filled blisters can last five to seven days. The rash heals by scabbing over.

People with monkeypox are infectious to others from the onset of fever until all lesions scab over.

"Monkeypox is in the same family of virus as smallpox, but it should not be confused with smallpox in levels of alarm," says Dr. Poland. "With smallpox, 10% to 30% of people can die. With this strain of monkeypox that is circulating right now, that death rate in Africa is 1% or less."

Protection from monkeypox

Dr. Poland believes people can be protected with smallpox vaccine.

"However, in the summer of 2019, a monkeypox-specific vaccine was approved in the U.S.," says Dr. Poland. "It requires two doses, four weeks apart, so you have to be immunized before being exposed."

Vaccinations for monkeypox are not available to the public. In the event of exposure, public health authorities will guide vaccination of close contacts, including healthcare workers.

Smallpox vaccines effectively prevent monkeypox if given before or within a few days of exposure. Other monkeypox therapies are tecovirimat and brincidofovir — both antiviral medications — and vaccinia immune globulin. These therapies were originally designed for smallpox but also work for monkeypox. All are available in the U.S. National Defense Stockpile.

Should you be concerned?

The average person should have near-zero concern, says Dr. Poland. First, transmission of monkeypox requires prolonged close contact with people who are infected. Unlike COVID-19, where people may not know they are infected, people infected with monkeypox have symptoms, such as fever or a rash, that make it easier to recognize. These symptoms cause people to seek out medical care.

The incubation period — the time from when a person is exposed to when that person develops symptoms — is long. Therefore, public health measures can help prevent additional cases.

Finally, vaccines can prevent infection. Treatments are available for those who get infected. He says for public healthcare organizations and scientists, there is concern at a global level.

"You would not want to see this virus, for example, mutate and become highly transmissible," says Dr. Poland. "The death rate for this virus is akin to what the death rate was for COVID-19 when it first emerged. COVID-19 is a far bigger threat."

There is a hypothesis why this virus is circulating, says Dr. Poland.

"This is the first time in modern human history where we have so many people who have never been exposed to a pox virus and have never been vaccinated against smallpox," says Dr. Poland. "Perhaps what the teaching point of this is the public is going to have to become scientifically and more microbiologically literate in understanding that with climate change, with very rapid international travel, with ignoring basic health recommendations, we will see one kind of outbreak after another."