Here it comes. The next storm, building collapse, infectious disease or other major disaster is breaking out. Are hospitals and healthcare organizations prepared? Do they have the people, resources, space and processes they need in place to provide patient care and save lives?

These critical medical care facilities must all plan ahead for such emergency events to be able to carry on care and safety for patients on-site or incoming. This requires members of several teams coming together to create a disaster or disease outbreak response plan, also referred to as an emergency operations plan1.

This type of plan should address several facets of operations and care, such as staffing, infrastructure, inventory, communication, cleaning and infection control, in order to best prepare, respond and protect patients, staff and others during emergency events. To be effective, the plan must be communicated, understood and practiced with staff before an event occurs.

As Janet L. Lumbra, Director, Business Development, Mobile Medical International Corporation (MMIC), puts it, “A carefully crafted Disaster Plan, which is constantly reviewed and updated and is accompanied by ongoing regularly scheduled training and testing, is the key to a successful disaster response.”

Plan preparation

Emergency operations planning involves a multi-faceted approach, including input from many individuals and departments within facilities.

“The administrative staff, supported by clinicians and facility planners, should be involved in disaster and outbreak planning,”2 advised Lumbra. “Successful pre-planning and incorporating the skill sets of all who can contribute to the most carefully thought-out plan will achieve the best overall results.”

Sharon Ward-Fore, MS, MT(ASCP), CIC, FAPIC, Infection Prevention Advisor, Metrex, calls for support from “all major stakeholders for planning, including administrative leaders, pharmacy, emergency department, laboratory, safety and security, nursing, physicians, patient throughput, EVS, escort services, dietary/food services, supply chain, materials management, surgical services, emergency management, communications, IT, morgue, facilities, just to name a few. All of these groups play a specific role in the day-to-day operations of a facility.”

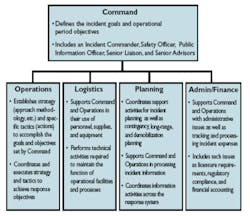

Some facilities may have dedicated support from an “’Incident Command System’3, managed by an Emergency Management department,” Ward-Fore noted. “They can use ‘tabletop’ or real-time events to help train and determine gaps in their planning. In these exercises, everyone has a specific role no matter the scenario. Training can be for incidents like mass casualties from radiation exposure, bombs, bioterrorism and events like active shooters, snowstorms or tornadoes.”

She added that “if there is no formal incident command system, then having all the major departments in a healthcare facility get together and assess their major systems – electrical, water, food, staffing – would be a good place to start. They should discuss different scenarios and determine how long they could continue to operate.”

Tapping the knowledge and information from subject matter experts (SMEs), taskforces and outside resources also can assist planning, points out Cole Stanton, Director of Education and AED Specification, ICP Group.

“There is the direct contingency planning task force, but where gears can start to grind is often at the level of the SME,” Stanton said. “For example, whether transmissible via fomite or not, surface hygiene is a crucial strategy to prep for an outbreak. But, while the healthcare facility has top-notch infection control and housekeeping professionals, they can’t specialize in translating what US EPA disinfectants do and don’t do, nor can in-house staff know likely supply/pipeline dynamics when an epidemic hits.”

Further, he recommends that, “every group should cultivate an on-call SME for disinfection associated with programs for SHEP (Surface Hygiene: Epidemic & Pandemic). Then consider what other SMEs the contingency planning group needs, make a list and start filling in the blanks. Call on your SMEs to participate in working groups, and this doesn’t have to involve expense. Restoration companies and their manufacturer suppliers are a great place to recruit expertise freely shared.”

Stanton explained that “SHEP is a concept created at ICP to cut through the noise and teach best practices of surface disinfection that can be flexed to accommodate circumstances. Whether the emergency is a hurricane coming ashore or a breakout of infectious disease, information is crucial.”

Power to care

Hospitals and healthcare facilities rely on essential utilities, technology and supplies to keep operations and care going. These all must be prepared for in advance of an emergency.

“Planning revolves around the components needed to keep the facility running, like in a power outage or caring for any causalities in the case of a mass casualty situation,” emphasized Ward-Fore. “Emergency power, water and food are first and foremost for the hospital staff and patients. Determining how long you can function once you lose power is really important.”

Lumbra also urges preparation for critical infrastructure and technology functions.

“Be sure to include contingencies in your plan in the event of power failure, lack of clean water or lack of computer access,” she stressed. “There may be patients who need dialysis (reference: the Hurricane Katrina response, which encountered this issue and was unable to respond due to the unavailability of clean water) or other services for which you should plan and include contingencies for in the Disaster Plan.”

Equipped to care

With regard to creating an emergency operations plan, Lumbra advises turning to the web and the knowledge of community emergency responders.

“There are many resources available to assist healthcare facilities in developing a disaster/outbreak plan that will best meet their needs,” Lumbra said. “Take advantage of online resources and tailor those resources to meet your needs; there is no need to re-invent the wheel. Work with your administrative staff and local disaster planners, i.e., fire department, police department, ambulance service providers and other emergency responders for important input to the development of the best disaster plan to meet your needs. They will know what they can provide and will make recommendations regarding what you should plan to provide.”

Lumbra outlines some of the many important considerations in preparing operations and care during a disaster or disease outbreak, including:

· The first step is to develop a Disaster Plan that includes inventory planning for the basic items, including personal protective equipment (PPE) for staff members who will be responding to the emergency.

· Have appropriate resources/medical supplies, including adequate blood supply, qualified staff available that are trained in the execution of the Disaster Plan and safe designated areas for patient care in the hospital or in a temporary facility.

· The Disaster Plan should include a list of medical equipment that is generally needed during an emergency situation (defibrillators, patient monitors, patient gurneys, exam lights, etc.), as well as medical supplies needed in an emergency (medical air, oxygen, oxygen masks, IV solutions, IV supplies, etc.). There should be considerations for proper storage of medications, some of which may require refrigeration.

· A staffing plan should be developed and put in place to ensure that staff is available throughout the emergency situation, without relying too heavily on just a few individuals who may ‘burn out’ if the emergency lasts for a prolonged period.

· In addition, you will need an ongoing plan to keep items stocked as the emergency progresses. Also needed are logistics of where items are stored and who has access to them, how prospective patients will be treated and how staff will be disseminated to provide the best possible coverage during the emergency. Determine if temporary on-site facilities will be required, i.e., trailer-based, tent-based, etc., and, if so, proper planning must be in place to acquire them quickly and efficiently.

· A critical aspect of any successful Disaster Plan is the ability to communicate. The use of technology, i.e., smart phones, computers, etc., should be utilized, if possible, but in the event the situation prevents the use of technology, the use of paper documentation should be an option that is included in the plan and is part of the training process.

· Above all, provide continuous training and testing in all aspects of the Disaster Plan to ensure that those expected to participate in the Disaster Plan are ready to respond when the need arises.

Controlling infections

In terms of disease outbreaks, Stanton highlights the cleaning and disinfection practices needed to maintain hygienic and safe healthcare settings.

“Touchable surfaces should be a focal point of consideration when addressing protection plans for your facility,” Stanton advised. “Humans touch their face on average 20 or more times per hour, with contact mostly to the skin, mouth, nose and eyes. We also touch common objects or shared surfaces, such as buttons, door handles, etc., approximately 3.3 times per hour, so surfaces are a crucial cause for consideration and concern. Having realistic, clearly defined plans and key performance indicators to define your success is essential to every organization. The same principle applies when dealing with a pandemic or an epidemic, which are increasing in frequency and lethality.”

Stanton points to federal guidelines in planning for infectious events, such as epidemics and pandemics.

“To paraphrase joint guidance on SARS-CoV-2 in 2020 from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), every individual or group responsible for an indoor environment where our people live and work must engage in three fundamental steps: Make a Plan, Implement the Plan and Never Stop Revising the Plan.,” he explained. “Plans are imperative in any facility and after the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, we better appreciate the dangers of extraordinary outbreaks, as well as the cost of preventable, ‘ordinary’ occupant sickness.”

Additionally, Stanton raises other questions that are “often forgotten in contingency planning, such as contact tracing for the subcontractors in healthcare facilities daily. How do we tighten up sign-in/sign-out procedures during an epidemic? How do we alter the chain of custody for externally introduced equipment and supplies when work is suspended due to rising community transmission? To respond quickly while maintaining CDC best practices, what should the procedure be for disinfecting larger areas with more complex geometry than housekeeping is used to addressing?”

Many measures and practices are needed for cleaning, disinfection and isolation to maintain healthy and safe medical environments during disasters and outbreaks, emphasizes Lumbra.

“Prepare for infection control by following the safety protocols in the Disaster Plan and having sufficient PPE, patient care supplies and cleaning supplies available, as well as following cleaning protocols supported by logistics to remove both normal and hazardous waste to keep areas infection-free and logistics allowing for deliveries of goods or services that may be required during the emergency,” she recommended.

“If access to utilities is a concern, ensure that the Disaster Plan includes generators, auxiliary HVAC units (preferably with HEPA filtration for proper air filtration), a potable water supply (perhaps a bladder, which can be refilled with potable water on a regularly scheduled basis), water pumps, etc. If isolation of contagious patients is a concern, ensure your Disaster Plan includes areas for patient care that can be isolated in order to protect other people from exposure.”

Response and reflection

Regarding response and support for COVID-19 and patient care, “Bridgeport Hospital recently received $3,818,190 in federal funds for emergency protective measures officials implemented to safeguard the health and safety of the public from COVID-19. FEMA provided funds through a grant from its Public Assistance Program to the hospital based in Bridgeport via the Connecticut Division of Emergency Management and Homeland Security. The grant reimbursed the non-profit hospital for eligible costs it submitted from Jan. 20 through Aug. 31, 2020,”4 according to a press release from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

“Reimbursement for treatment and care of COVID-19 patients included providing equipment for testing, renting stretchers and beds, developing in-hospital surge areas, adding 36 isolation rooms, buying and transporting medical equipment and supplies, disinfecting facilities and purchasing personal protective equipment for hospital workers. Other costs included setting up and staffing a command center, two temporary triage tents and two specimens-collection sites,” 4 the FEMA release continued.

Additionally, after several disasters, Mobile Medical International Corporation has supplied Mobile Surgery Units to facilities to continue care, notes Lumbra.

“In 2011, we responded with two Mobile Surgery Units to Joplin, Missouri’s St. John’s Regional Medical Center when their entire hospital was destroyed,” she shared. “Our Mobile Surgery Units provided a year of on-site surgical space while they rebuilt their facility.”

Medical supply access stands out as a lesson from COVID-19 for Ward-Fore.

“We learned that shortages can occur that can impede patient care, so we need to have a stockpile of critical items available or be flexible in what we have and how we use it.”

Stanton observes room disinfection equipment access as another area of education.

“SARS-CoV-2 has shown us the limitations of electrostatic and ultraviolet, while introduced us to the efficiency of airless spray and foaming,” he addressed. “How can we assure access to these delivery method devices without warehousing? Can we work with suppliers to conduct hands-on training in advance so that can then translate into train-the-trainer capability when an outbreak is looming?”

In the end, facilities must ultimately rely on their plan in place, no matter what event is on the horizon, shares Lumbra.

“You are never totally prepared because there is no way to predict the exact nature of the emergency until it actually occurs,” she said. “Sometimes, the disaster is so totally unexpected and sudden that all you can do is use the disaster plan you have and adjust it as needed during the response. Review of the after action and lessons learned from other disasters can help you to identify the shortcomings that were identified in those Disaster Plans, which can help you to develop the best possible Disaster Plan for your area.”

References:

1. HCO Emergency Operations Plan, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/mscc/handbook/chapter2/Pages/hcoemergen.aspx

2. “It Takes A Village” – “Preparing for Outbreaks and Catastrophes” – HPN Article 6/19/2019 by Susan Cantrell, It takes a village - Preparing for outbreaks and catastrophes | Healthcare Purchasing News (https://www.hpnonline.com/infection-prevention/article/21084697/it-takes-a-village-preparing-for-outbreaks-and-catastrophes)

3. Emergency Management and the Incident Command System, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/mscc/handbook/chapter1/Pages/emergencymanagement.aspx

4. Connecticut’s Bridgeport Hospital Awarded More Than $3.8 Million in Third Pandemic-Related Emergency Response Reimbursement, https://www.fema.gov/press-release/20210625/connecticuts-bridgeport-hospital-awarded-more-3-8-million-third-pandemic

About the Author

Ebony Smith

Ebony Smith was previously Managing Editor for Healthcare Purchasing News.