Black Americans are getting vaccinated at lower rates

Black Americans are receiving COVID vaccinations at dramatically lower rates than white Americans in the first weeks of the chaotic rollout, according to a new KHN analysis reported by Hannah Recht and Lauren Weber in a story online at Kaiser Health News.

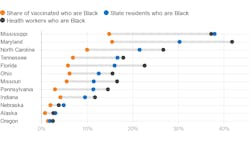

About three percent of Americans have received at least one dose of a coronavirus vaccine so far. But in 16 states that have released data by race, white residents are being vaccinated at significantly higher rates than Black residents, according to the analysis — in many cases two to three times higher.

In the most dramatic case, 1.2 percent of white Pennsylvanians had been vaccinated as of January 14, compared with 0.3 percent of Black Pennsylvanians. The vast majority of the initial round of vaccines has gone to healthcare workers and staffers on the front lines of the pandemic — a workforce that’s typically racially diverse made up of physicians, hospital cafeteria workers, nurses and janitorial staffers.

If the rollout were reaching people of all races equally, the shares of people vaccinated whose race is known should loosely align with the demographics of healthcare workers. But in every state, Black Americans were significantly underrepresented among people vaccinated so far.

Access issues and mistrust rooted in structural racism appear to be the major factors leaving Black healthcare workers behind in the quest to vaccinate the nation. The unbalanced uptake among what might seem like a relatively easy-to-vaccinate workforce doesn’t bode well for the rest of the country’s dispersed population.

Black, Hispanic and Native Americans are dying from COVID at nearly three times the rate of white Americans, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analysis. And non-Hispanic Black and Asian health care workers are more likely to contract COVID and to die from it than white workers. (Hispanics can represent any race or combination of races.)

“My concern now is if we don’t vaccinate the population that’s highest-risk, we’re going to see even more disproportional deaths in Black and brown communities,” said Dr. Fola May, a UCLA physician and health equity researcher. “It breaks my heart.”

Dr. Taison Bell, a University of Virginia Health System physician who serves on its vaccination distribution committee, stressed that the hesitancy among some Blacks about getting vaccinated is not monolithic. Nurses he spoke with were concerned it could damage their fertility, while a Black co-worker asked him about the safety of the Moderna vaccine since it was the company’s first such product on the market. Some floated conspiracy theories, while other Black co-workers just wanted to talk to someone they trust like Bell, who is also Black.

But access issues persist, even in hospital systems. Bell was horrified to discover that members of environmental services — the janitorial staff — did not have access to hospital email. The vaccine registration information sent out to the hospital staff was not reaching them.

“That’s what structural racism looks like,” said Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. “Those groups were seen and not heard — nobody thought about it.”

UVA Health spokesperson Eric Swenson said some of the janitorial crew were among the first to get vaccines and officials took additional steps to reach those not typically on email. He said more than 50 percent of the environmental services team has been vaccinated so far.

Public health messaging has been slow to stop the spread of misinformation about the vaccine on social media. The choice of name for the vaccine development, “Operation Warp Speed,” didn’t help; it left many feeling this was all done too fast.

In Washington, D.C, a digital divide is already evident, said Dr. Jessica Boyd, the chief medical officer of Unity Health Care, which runs several community health centers. After the city opened vaccine appointments to those 65 and older, slots were gone in a day. And Boyd’s staffers couldn’t get eligible patients into the system that fast. Most of those patients don’t have easy access to the internet or need technical assistance.

And the lack of public data makes it difficult to spot such racial inequities in real time. Fifteen states provided race data publicly, Missouri did so upon request, and eight other states declined or did not respond. Several do not report vaccination numbers separately for Native Americans and other groups, and some are missing race data for many of those vaccinated. The CDC plans to add race and ethnicity data to its public dashboard, but CDC spokesperson Kristen Nordlund said it could not give a timeline for when.

One-third of Black adults in the U.S. said they don’t plan to get vaccinated, citing the newness of the vaccine and fears about safety as the top deterrents, according to a December poll from KFF. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.) Half of them said they were concerned about getting COVID from the vaccine itself, which is not possible.

Experts say this kind of misinformation is a growing problem. Inaccurate conspiracy theories that the vaccines contain government tracking chips have gained ground on social media.

Just over half of Black Americans who plan to get the vaccine said they’d wait to see how well it’s working in others before getting it themselves, compared with 36 percent of white Americans. That hesitation can even be found in the health care workforce.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.