Becoming sustainably significant in purchasing “green” products may seem simple enough. Look for the environmentally friendly or preferred label/sticker and you’re good to go green.

Unfortunately, that strategy and tactic may show people just how green you really are — and not in a good way.

During an educational session here at the annual conference of the Association for Healthcare Resource and Materials Management (AHRMM)in Washington, DC, two supply chain experts with sustainability experience shared their lessons learned about an organization-wide initiative spanning a product category as well as how those in the audience could set up their own projects.

Nancy Anderson, Vice President, Contracting, Greenhealth Exchange, and Christy Naughton, Communications Manager, Supply & Resource Management, Dignity Health, shed some light on what it means for a healthcare organization to go green, why it’s important and how it’s measured. Both also identified the challenges of embarking on a sustainability initiative and the tools and resources needed to pave the way.

Justifying a sustainability initiative that calls for purchasing green products and services and changing workflow behaviors seems to be a no-brainer in context, according to Anderson.

“Healthcare organizations have a large carbon footprint,” she said. “They use a lot of energy and generate a lot of waste and gas emissions. In fact, hospitals tend to be one of the most energy-intensive buildings as they take care of patients.”

Anderson then tapped into the physician’s creed: “In healthcare, clinicians hold fast to the rule to ‘first do no harm,’” she said. “Chemicals of concern in products can lead to and contribute to certain diseases. Poor air quality can lead to and contribute to asthma. We need to control, if not eliminate, these issues.”

Anderson emphasized five attributes that make a product green or sustainable.

- Minimizes environmental impact (“footprint”)

- Contains no chemicals of concern/eliminates toxicity

- Reduces waste

- Positively contributes to the environment and our relationship with it

- Ensures natural assets continue to be available

Nearly a year ago, Anderson and GX started working with Dignity Health and Naughton to launch a sustainability initiative focused on a single product area where they could identify green products and develop a “green formulary.”

With their green parameters in hand, they chose office supplies as their first effort at Dignity and set up their program before bringing their supplier Staples into the mix.

To launch the effort, Dignity and GX pulled together a variety of subject-matter experts to discuss the initiative and overall plan to carry it out.

“Projects like this call for collaboration among of a lot of people because different experiences from experts can help form good decisions,” Anderson indicated. She encouraged those mulling sustainability projects to conduct a lot of research and use the data and work already done by others as a baseline. She cited Health Care Without Harm and Kaiser Permanente among the leaders.

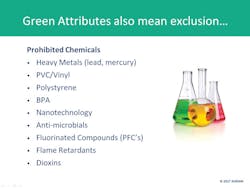

The mark of an effective sustainability initiative is rooted in an organization’s definition of green, according to Anderson. That includes listing examples of green attributes — what’s included and excluded [See slides 1 and 2] and how to verify those attributes through independent third-party organizations that certify labeling. [See slide 3.]

Slides courtesy: Greenhealth Exchange and Dignity Health, July 2017.

“Much depends on how thorough you want to be,” Anderson advised. “These independent organizations can show if a product just has one single sustainable attribute vs. multiple sustainable attributes. For example, you may not want to accept something that includes recycled content, but also contains vinyl or PVC. You have to determine your own threshold of acceptance and your own definition of green/sustainable. The organizations that independently assess and validate green claims do a deep dive for you.”

What Anderson and Naughton learned as the office supplies sustainability project progressed is that office supplies spanned a range of product categories that included desk supplies, break room supplies, cleaning supplies, office equipment and promotional items, among others. The lack of homogeneity didn’t deter them from their mission.

“You need to see and understand where the green elements and attributes are in these products,” Anderson said. “Your supplier partner(s) should be able to help you with this. They need to work with you and the standards you have defined and set. You need to determine and verify products that are truly green. Something that carries an ‘Energy Star’ designation is different than something that carries an ‘Energy Smart’ designation, for example, because those designations mean different things. You need to understand what they mean and whether they meet the green standards you have set for your organization, whether single attributes are acceptable or multiple attributes are required for acceptability.

“Supplier claims about green attributes should be verified,” she insisted. “Know what those certifications mean.”

Even within the office supplies “multi-category,” products fell within a certain range, according to Naughton. The classification included products that weren’t really green to ones that were the greenest. For example, Dignity and GX learned that for laser printer toner, low-yield new toner was not green but high-yield new toner offered slightly more green opportunities. Meanwhile, low-yield remanufactured toner represented a greener improvement over the other two, but high-yield remanufactured toner represented the greenest option because it could be refilled the most and used for a longer period of time.

“Green is a spectrum,” Anderson said. “There are a lot of green products along the way with increasingly green attributes. In this case the high-yield remanufactured toner is the greenest because it reduces garbage and increases usage. The same goes for virgin paper vs. recycled paper, new vs. refillable pens vs. refillable pens with post-recycled consumer content.”

Cost conundrum

Anderson acknowledged that the cost equation for green products looms large.

“Getting to green without spending more can be a challenge,” she said. “For example, we found that some green items cost more. Tissues were 25 percent higher, brown clasp envelopes 26 percent higher, stick pens 21 percent higher and easel Post-It pads 19 percent higher. We’ve had to accept those increases but managed to negotiate volume discounts to offset the higher pricing. However, some green items were cheaper. For example, printer ink was 27 percent lower, self-inking stamps 14 percent lower, retractable pens 30 percent lower and recycled paper

10 percent lower.”

The challenge with refillable retractable pens is educating people on following protocols and not treating these products as disposable — as in throwing them away before grabbing another one, Naughton said. “It’s definitely not easy,” she added, “and takes time to educate people to change behaviors.”

Anderson stressed the value of contract negotiations. “You have to negotiate lower pricing on your highest-use items,” she noted. “You may have to pay more for some green items. You just have to manage your product mix and green formulary to maximize your green efforts and generate savings by moving to a market basket of green items.”

Anderson cited three hospital members who started green conversion efforts and by the end when they had dedicated more than 60 percent of their purchases to green products they generated annual savings of $54,000, $267,000 and $1.2 million, respectively.

“Cost savings is achievable,” Naughton said. “Discounts and savings do exist.” Naughton oversees staff participation in this project from 39 member facilities. The effort requires engaging employees, changing behaviors and emotions and reinforcing practices, she noted.

“We set up a clear objective, identifying what we wanted to do and why, and delivered a consistent message that shared ongoing results of how patients and staff were affected,” Naughton said. “This really comes down to showing why this is important and how it contributes to patient care.”

One of the more surprising hurdles to conversion efforts mirrored physician preference: Emotional attachments to preferred products.

“You think: How hard is it to change a pen?” Anderson asked. “But then they changed my paper pads to yellow with no red lines from white with red lines. It threw me because I had been using the same thing for 30 years. You need people to understand why you’re changing their products. What is the value of the change if workflow is affected?”

Dignity focused on office supplies first because “they touch every one of us,” Naughton said. “We tied our efforts into the CQO movement and set up a template. Feedback is important as is cultivating a user group to serve as champions of the effort.”

Ultimately, GX worked with Dignity to convert 855 products to green models, according to Anderson. They also worked to nurture a culture that identified things like PVC and antimicrobials as something to question that affects patients, staff, visitors and the community at large. GX and Dignity both plan to expand their efforts into other categories, Anderson indicated. This includes paint, lighting, electronics, medical supplies, cleaning supplies, food, biodegradable products and composting.

Audience members expressed concern about GX’s and Dignity’s migration away from antimicrobial-coated products, such as ceiling tiles, keyboards and other products, as well as hand sanitizers, and running afoul of an organization’s infection prevention nurses.

Anderson acknowledged that infection preventionists may not be comfortable with removing and no longer buying antimicrobial-coated products to prevent cross-contamination based on competing and conflicting expert opinions and studies. “You need to include infection prevention nurses in your interdisciplinary group to participate in that decision before eliminating antimicrobial products,” she said. “We’ve found in our research that when it comes to antimicrobials in products the negatives outweigh the positives. But you need to consult with your infection control nurse on that for your organization.”

Naughton said Dignity’s infection control nurses are discussing options with the group.

About the Author

Rick Dana Barlow

Senior Editor

Rick Dana Barlow is Senior Editor for Healthcare Purchasing News, an Endeavor Business Media publication. He can be reached at [email protected].