If there’s one bit of positive news Healthcare Purchasing News readers can take to the bank while battling a pandemic and navigating through product shortages and sourcing options it’s this: Compensation levels – at least for now – by and large, offer an affirmation of value.

Here are some welcoming takeaways from HPN’s 2020 Supply Chain Compensation Survey.

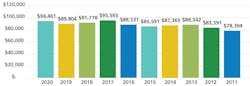

2020 Overall Compensation Composite Index:

The overall compensation composite index rebounded this year after slipping in 2019, erasing last year’s losses and exceeding even the previous year’s gains. (CCI is derived by the average aggregate salary of all survey respondents.) But against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 will this turn out to be a ricochet next year? We’ll see.

This year’s survey achieves a bit of history as the average salary for a Director and Manager of Materials Management/Supply Chain punched through the six-figure ceiling for the first time in all the decades HPN has conducted this survey. Department leaders reported an average annual salary of $101,174, a whopping 7.5 percent gain over 2019’s average of $94,096.

Not to be outdone, the higher-level Supply Chain leaders also recorded impressive gains. Executive/Senior/Corporate Vice Presidents reported an average $206,000 this year, compared to $153,421 in 2019. At the top of the leadership chain, the Chief Purchasing/Supply Chain Officers recorded $239,500 on average in 2020, up from $187,500 last year, according to the survey.

Two other titles – Value Analysis Director/Manager/Coordinator and O.R. Materials Manager/Business Manager – reported respectable gains in the four-digit realm. The former’s compensation increased to $89,500 in 2020 from $67,167 last year; the latter rose to $70,938 this year from $67,167 in 2019. Another noteworthy result with these two titles? Females outpaced males in average compensation, the survey showed.

Of the eight titles that HPN typically surveys for compensation data, three reported decreases.

Purchasing Directors/Managers saw their compensation sink to $71,875 this year from $76,484 in 2019. Compensation for Senior Buyers/Buyers/Purchasing Agents slipped to $52,500 in 2020 from $54,868 last year, according to the survey. Meanwhile, compensation for those with MMIS/Supply Chain Informatics Manager titles slid to $62,500 from $78,750.

As an ongoing customary cautionary caveat, HPN advises readers that survey data and trending perspectives hinges on a variety of demographic elements that include the number and mix of respondents by job title, facility type and location and gender. For example, more senior-level executives who lead centralized integrated delivery network (IDN) operations generally will elevate salary data, while more buyers at community hospitals may push the salary data lower.

Still, HPN continues to monitor five key trending areas that make this more than just a numbers game.

Let’s start with the most overt statistic.

Gender

Men still make more than women across the board. This has been consistent for decades even as the gap between the two periodically narrowed then widened.

“One thought is that maybe a larger majority of women come in as entry level versus males that may have an edge on experience – longevity in the field – when they advance,” she observed. “The disparity is more evident at higher level positions. The concentration of males at higher level positions could be influencing the statistic. Interestingly, the trend is reversed in the value analysis positions. Because of the clinical knowledge desired, many of these positions are filled by nurses whose jobs in nursing probably commanded a higher salary before they moved in to the role, and because there are many more female nurses than male, the females in these positions are seemingly compensated better.”

Templeton’s organization earned HPN’s Supply Chain Department of the Year Award in 2008.

“In all the organizations I’ve worked in, it seems that gender neutrality when it comes to [compensation] decisions remains a priority,” he noted. “I’d never want to work for an organization and/or be a leader that allowed this sort of thing. Unfortunately, the data doesn’t prove this out as an industry-wide practice.”

Hardin argues that education foreshadows change, leaning toward parity.

“Keeping in mind that supply chain undergrad and graduate programs are a relatively new phenomena, I believe we’ll see greater equality as many more women are being educated,” he continued. “In fact, I taught last summer at a local university’s supply chain program, and nearly half the students were women. Many leaders like myself didn’t have such programs, and I believe that in a matter of a few short years that focused education in supply chain will serve as the great equalizer.”

Hardin served as the leader of HPN’s 2016 Supply Chain Department of the Year, CHRISTUS Health.

“I know what we pay our employees, at least on my team, and we just don’t see this trend among our team,” Colonna told HPN. “I am not saying this is not a real issue in the rest of the industry – just that we are not seeing it here. In part it may be that our team focuses on the skill set and characteristics and then the job experience. Is this person a good fit for the role and the organization? Is the organization a good fit for the person? Our H.R. team does a good job as well, looking at the background of the individual. The H.R. [compensation] team makes the recommendations on salary based on market research and, as far as I know, the fact that it is a man or woman, is irrelevant to that research. I know that it has never occurred to me to even think the pay grade should up or down based on a person’s gender.”

Colonna’s organization earned HPN’s Supply Chain Department of the Year Award in 2018.

Age, Experience, Longevity

This trend seems to indicate that the more experience you gain, which can take years, and/or the longer you stay within an organization, which can generate influence and power, the more you can earn. As a result, supply chain professionals weigh the decision between migrating frequently from organization to organization to advance/elevate a title, compensation and career versus remaining longer with fewer organizations, including spending an entire career in a single place.

Experts remain mixed and somewhat nonplussed that this even should be considered an issue.

Hardin rebuffs any implication that either tactic offers more of an advantage.

“The experience one gains from working in multiple organizations, and subsequently the wide array of experiences, has been truly invaluable in the trajectory of my career,” he admitted. “I don’t know for [a] fact that I’m paid less but I do know that I’m paid fairly and well above the average. Perhaps longer tenures would have landed me in larger organizations, but I must say that many of my moves have been for reasons that were heavily personal and I would change very little.”

Of course, the higher you go the fewer opportunities to move may exist, according to Colonna.

“Typically, the trend is that if you want to see a large pay increase, in a short time, you have to change organizations,” Colonna noted. “However, over a long term, you can see a steady increase due to merit or cost of living. It may only be three percent a year but you figure that over 20 years, as your salary grows, so does that three percent number. In senior leadership, for VP and above type roles, there are only a few open every year. If you are already in a senior role and happy, the incentive would have to be pretty good to move.”

Templeton agrees that either avenue can provide value.

“The longevity within an organization can be an advantage,” she indicated, citing herself as one example. But she adds that a number of factors could influence someone’s reason to move around. They include:

- Personal reasons for relocation.

- Culture of the organization. “Do they promote from within or have the idea that new blood is better?”

- Variety of responsibilities that could expand your portfolio and bring value, if this can’t be gained within your current organization.

- Average age of those “above” you and impact on opportunity for advancement.

- Opportunity extended from previous boss or mentor.

“I feel you need to stay within a role long enough to make an impact and learn from the experience, rather than ‘job hop’ just for the title,” she added.

Education, Training, Certification

The trend seems to indicate that the higher education you receive – including degrees and learning new skills and thinking – the higher your income trajectory.

Hardin expresses support for the idea but remains cautiously optimistic that quality learning will contribute to the process.

“It should absolutely contribute, but I believe to some degree that we’ve cheapened our education through the increased level of virtual education,” he said. “I’ve taught in higher education environments and consistently receive feedback from students that in-person courses, and particularly my classes, are better received than virtual classes. Point of fact, I’m much more discriminating about candidates for hire that did the majority of their education online. I’ve seen a strong correlation between intensely online coursework and the lack of capabilities and maturity. So, while I believe that education can serve to positively turn the dial on one’s trajectory, I believe it’s the type of education one is receiving that can make a difference.”

Pandemic-motivated closures of “live” educational events, of course, remain the X factor.

“I feel that those with higher education have more ‘polish on the apple,’” Templeton quipped. “The journey to advanced degrees, especially if you are working, forces you to develop skills that become useful once school is over. These include time management, focus, oral and written communication skills, working within teams – if [the] program requires project completion – organizational skills and sharing experiences with others. [It] allows you to expand the way you think, and at the end the satisfaction and pride of completing the journey.”

Templeton further acknowledges that many human resources compensation schemes include higher education requirements on a job to be equated with justification for higher pay. “There are some organizations that are driven by ‘pedigree’ and some candidates would not even pass résumé acceptance without an advanced degree,” she added.

But that pedigree can be a crutch as much as a barrier, Colonna warns.

“As H.R. processes and systems become more automated, it becomes harder for candidates to apply for mid-manager and above roles,” he said. “Internal recruiters will not consider anyone who does not have a BA or MBA, if the [job description] has those requirements. This is unfortunate because I still believe that much of healthcare supply chain is an [on-the-job-training] profession. I am not saying there is not value in higher education; I am just saying that we may be losing valuable candidates because of basic requirements that we have added to [job descriptions].”

Colonna contends that a degree may represent a rite of passage to some.

“I also think there is this somewhat narrow-minded belief among some leaders, ‘if I had to get a degree, you have to have a degree,’” he continued. “I would say that there are long-time supply chain professionals who do not have degrees that still deserve a shot at leadership positions. Having said that, I do believe and would recommend that younger professionals should seek out higher education and degrees because it will open more doors for them.”

Sargent stresses that education and experience can achieve something close to balance when evaluated for leadership positions.

“I contradict myself when I say education is important as I don’t have an advanced degree,” she admitted. “I do, however, have years of experience that is acquired though a career. I do feel that the need for ongoing learning is foundational to a well-rounded leader. Certification validates your knowledge of the supply chain. The ongoing education required to maintain certification is an advantage to the person who is looking to move up.”

Still, education remains profitable, Templeton emphasizes.

“Education is something that no one can ever take away from you once you have it,” she asserted. “It is worth the investment in yourself.”

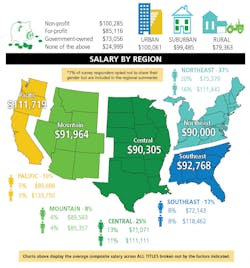

Hospital Type, General Location

This trend seems to notate that the higher-compensated Supply Chain executives and professionals entrench themselves at larger urban not-for-profit hospitals, followed by suburban not-for-profit hospitals and then for-profits. Of course, some of that may be attributed to the smaller number of for-profit hospitals within the overall hospital market – they comprise about 15 percent to 20 percent of the total.

Hardin chuckles at the statistics.

“I wasn’t aware of the trend but can tell you that my favorite environment thus far is being in an urban, academic medical center,” he said. “I place significant value on work-life balance and with that I want my work to be interesting and purposeful. I’ve found that I can best meet my professional needs by working in an urban setting that’s intensely academically focused.”

Sargent attributes any disparity to the business and economic models, seasoned with lifestyle elements.

“The not-for-profit organizations focus on generating income for the organizations versus the for-profits generating income for their stakeholders,” she surmised. “Salaries in a for-profit dig into the pockets of the stakeholders. The larger urban and suburban areas have a higher cost of living, which generates the need for higher pay. It is also a lifestyle – those that live in these communities rather than in rural areas prefer that lifestyle and vice versa.”

Templeton concurs to a point.

“Some of this compensation follows cost-of-living trends that just naturally would just pay more,” she said. “Larger organizations come with expanded responsibilities and require you to manage more risk, which is a draw for those that feel they want a larger venue to practice. Also, matching your desired lifestyle could drive the locations and organizations that you target. Just the name/prestige of an organization alone can be a draw to executives that see or realize other benefits that come from that recognition. Generally, the not-for-profit sector allows more autonomy in creating and running a shop than for-profits that dictate and manage from a corporate perspective, and financials are the main driver of performance operations versus a focus on patient care and quality first. Altruistically, there needs to be a match of your mission to the organization mission. That alignment is important for success.”

Geography

HPN’s annual survey, rather consistently over the years shows that to earn the highest income, Supply Chain executives and professionals typically work in the Pacific region (largely, the West Coast) or in the Northeast (largely, New England down to the Mid-Atlantic states) with the perennial underdog sporadically unseating either of the first two being the Southeast (largely led by Florida).

Sargent points to “population density and higher cost of living” as likely causes.

Templeton agrees. “Some of this is driven by higher cost of living and concentration of larger IDNs and academic medical centers in certain geographies that drive greater opportunity,” she noted. “The movement across the country could also be influenced by the age of candidates that may cause more migration to a certain sector from time to time.”

In addition to cost of living, competition most likely is prevalent, according to Colonna.

“In those areas, there tends to be a large concentration of competitive healthcare providers,” he observed. “This likely creates a more competitive market for potential employees.”

Hardin expresses contentment with his own geographic choices.

“I never managed to move much beyond middle America, though I tried,” he said. “The higher incomes in the northeast are likely driven by cost of living, and the desire to move to Florida is likely a combination of cost of living and warmer weather. I happen to love middle America and can’t imagine at this stage in my life living and working anywhere else.”

About the Author

Rick Dana Barlow

Senior Editor

Rick Dana Barlow is Senior Editor for Healthcare Purchasing News, an Endeavor Business Media publication. He can be reached at [email protected].