The question of whether an instrument manufacturer’s instructions for use (IFU) for sterile processing have been “validated” is one of hot debate. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires manufacturers to provide customers with IFUs that describe in detail “instructions for a reprocessing method that reflects the physical design of the device, its intended use, and the soiling and contamination to which the device will be subject during clinical use.”1

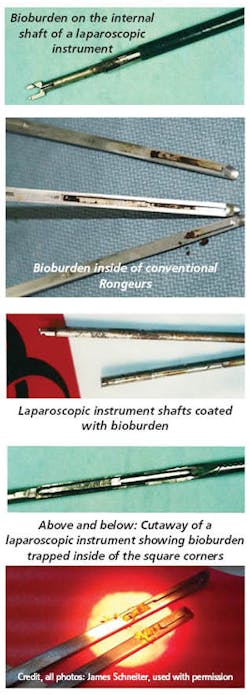

But do the IFUs take into account real-world conditions? Or do they simply demonstrate that a device “should” be sterile because an indicator confirmed that sterilization conditions were present? What about residual bioburden and biofilm remaining on devices? Does a central sterile/sterile processing department (CS/SPD) technician really have all of the information and tools he/she needs to truly rid an instrument of bioburden/biofilm prior to sterilization — soils that are invisible to the human eye? Especially with complex, laparoscopic instruments that must be disassembled, cleaned and reassembled prior to sterilization?

In this article we explore this issue and present insights from the FDA, industry thought leaders, CS/SPD professionals and manufacturers.

The FDA Takes Action

In March 2015, following the highly publicized superbug outbreaks linked to contaminated duodenoscopes, the FDA issued its guidance entitled: Reprocessing Medical Devices in Health Care Settings: Validation Methods and Labeling, Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. The document is intended to provide guidance to medical device manufacturers in their development of reprocessing instructions that “ensure that the device can be used safely and for the purpose for which it is intended.”1

“Residual soil, like blood and tissue, and bioburden deposited on a device after patient use may not be visible, so the FDA recommends that device manufacturer’s labeling instructions be based on rigorous testing of their cleaning and high-level disinfection or sterilization processes,” said Steven Turtil, a biologist in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “The 2015 Guidance recommends that manufacturers design their validation testing to assess device cleanliness after simulating worst-case scenarios of real-world soiling, followed by worst-case implementation of the cleaning instructions (such as using too little detergent).”

“Similarly, FDA guidance recommends validating sterilization steps by testing in worst-case, real-world scenarios,” he added. “For example, a worst-case scenario includes testing a large population of microbes that are highly resistant to the sterilant to determine the effectiveness of the sterilization or high-level disinfection process. The guidance recommends that test designs include multiple cycle testing to address potential soil accumulation that might result from multiple uses.”

Turtil explained how the guidance also recommends that manufacturers design their devices to be disassembled in order to gain access to components that may trap soil and contaminated tissue, stating: “Manufacturers should consider validation testing for such complex and difficult to clean devices, and such testing and reprocessing instructions should be accurately reflected in the labeling.”

“If you go back even six years ago there was a lack of recognition of IFU importance but recent outbreaks linked to unclean surgical devices have put an intense focus on this issue,” said Cynthia Spry, MA, MS, RN, CNOR(E), CSPDT, Consultant. “The healthcare industry has begun to recognize IFU importance and how problematic they are. The FDA is now trying to make sure manufacturers provide sterile processing technicians what they need to make sure devices are effective and safe for use.”

But what does IFU validation mean?

“When it comes to sterile reprocessing the most misused and misunderstood word in our industry right now is the word ‘validated,’” said James Schneiter, Founder, America’s MedSource. “I say that because a majority of reusable instrument manufacturers state that their IFUs have been ‘validated.’ But when you read their IFUs all they actually say is that their instruments were ‘sterilized’ at a given temperature, time and pressure. When the instruments emerged from the sterilizer the sterilization indicator showed that sterilization ‘conditions’ were present. What this means is that when they ran a load of their instruments, the conditions were right for sterilization. They never addressed whether or not the instruments were free of bioburden, and more importantly biofilm.”

While the FDA’s March 2015 guidance is a step in the right direction, it is important to note that it only applies to manufacturers seeking 510(k) approval for new reusable medical devices and that it does not apply to products already on the market. The guidance states:

“For 510(k)s, FDA expects manufacturers of a subset of devices listed in Appendix E to include data in 510(k) submissions to validate their reprocessing instructions. Validation data may be also requested as needed for substantial equivalence for other devices. For IDEs, a summary of the validation reprocessing instructions and methodology should be provided.”1

“The FDA finally did come out and say that from that date forward if a manufacturer wants 510(k) approval on a new reusable medical device, it must include a validated IFU with its submission,” said Schneiter. “That validation must follow all of the FDA required validation steps including how to decontaminate, clean and sterilize the device, and then go back post reprocessing and calculate the amount of residual bioburden on the instrument. That’s a great requirement for new products, but what about the tens of thousands of different surgical instruments that have not been validated and are being used on patients everyday?”

“I still see instruments in use that have no IFUs,” said Spry. “It really is a sticky issue because what do we do about the devices that are necessary for surgery but have no instructions for processing?”

Challenges to clean

There is clear evidence that some devices harbor dangerous bioburden and biofilm even when CS/SPD professionals follow a manufacturer’s IFUs for reprocessing. Most of us have seen photos of contaminated devices in the media and during presentations at industry conferences. The vast majority of CS/SPD professionals have likely experienced this challenge first hand. Inadequate cleaning of complex reusable instruments is such a major concern in healthcare that it made the No. 2 spot on the ECRI Institute’s Top 10 Health Technology Hazards for 2017.2

“Over the last decade in the U.S. we have quadrupled the use of antibiotics prophylactically both pre and post surgery,” said Schneiter. “Additionally, hospitals have spent billions of dollars improving OR sterility through new air handling systems, improved sterile drapes, gowns and other products. When it comes to laparoscopic procedures, almost every hospital in the country has done away with reusable trocars and only use single-use, disposable trocars. Accordingly, it would appear that the primary method of depositing bioburden into the deep organ cavity during a laparoscopic procedure is through the reusable laparoscopic instruments.”

“When you dive into the CDC data, you see that the rate of deep organ surgical infections in the U.S. has remained pretty much constant over the last decade,” Schneiter added. “I don’t think you need a PhD in microbiology to understand that non-validated, reusable laparoscopic instruments are a major part of the problem. Take-apart instruments were introduced to help solve the problem of deep organ surgical infections over a decade ago. If they really helped, we should have seen a reduction in the CDC deep organ surgical infection numbers. Just because an instrument has been validated to be sterile when it comes out of the sterilizer doesn’t mean that it is free of bioburden and is safe for use, unless its cleaning IFU has been validated as well.”

Whenever there is a highly publicized outbreak resulting from contaminated devices there follows a barrage of finger pointing in an attempt to assign blame. Did the outbreak occur because CS/SPD staff didn’t properly reprocess the instrument according to the manufacturer’s IFU? Is the manufacturer to blame because its IFUs were impossible to follow in a real-world setting, were too vague or confusing, or were inadequate for instructing CS/SPD professionals on reprocessing the device? Or perhaps the manufacturer is marketing a product that is far too complex to safely reprocess?

“This issue affects me on a regular basis,” said Casey Czarnowski, SPD Educator, Essentia Health Hospital, Fargo, ND. “In my small (31 FTE) SPD, each member of the management team of the SPD has to wear multiple hats. At the same time, we attempt always to follow best practices, and securing IFUs is a big part of that.”

Device complexity

Devices have become far more complex in recent years with the proliferation of minimally invasive surgical procedures — and therefore have become more challenging to clean — even when the manufacturers have developed their IFUs in accordance with the FDA’s latest guidance. Many have questioned whether some complex instruments are simply impossible to clean in the sterile processing environment.

According to Gene Ricupito, Partner, C&R Healthcare, the vast majority of surgical instruments in a typical hospital’s inventory don’t have complex componentry and can be effectively reprocessed through steam sterilization. He says the real problem is the “outlier instruments” that can’t be reprocessed in this way. Ricupito adds that he sees this challenge more often in academic medical centers that are conducting research versus community hospitals, stating:

“In some cases, medical device manufacturers working with clinical stakeholders in academic healthcare to develop new technologies may not have as much experience with presenting instructions for use that match the real-world processing environment. This is particularly true for start-ups.”

Schneiter points out that a major limitation to many manufacturers’ IFUs is that they require a CS/SPD professional to visually inspect an instrument after cleaning for bioburden and/or biofilm prior to sterilization. For some complex instruments that means disassembling them to both clean and inspect. But the dirty little secret is that this residue is invisible to the naked eye — making the task physically impossible.

“Let’s assume you have a very highly educated and motivated CS/SPD technician and he/she is manually disassembling every take apart instrument to remove bioburden and biofilm,” said Schneiter. “Then according to the IFU he/she is supposed to visually inspect to ensure all bioburden and biofilm have been removed. That is physically impossible to do with the human eye. It’s the dirty little wink wink, nod nod in our industry. It’s the sad reality of what people in CS/SPD face — they are held accountable for returning clean, sterile, moisture free instruments up to the OR and yet they are dealing with instruments who’s cleaning IFUs have never been validated and they are having to rely on visual inspection, which is not an acceptable technique.”

Lost in translation

Ricupito says another challenge comes with complex devices that are developed outside of the U.S. where the standards of reprocessing can be different, or simply articulated differently.

“For example, a device manufacturer in Germany and one in the U.S. might describe steam sterilization parameters that mean the same thing but because they articulate them in different ways it causes confusion for the CS/SPD,” said Ricupito. “The U.S. manufacturer might state a four-minute steam sterilization exposure time, while the German manufacturer states five minutes.

“But it turns out the U.S. manufacturer is referring to the end user variable exposure time, whereas the German manufacturer is referring to the total exposure time,” he adds. “Steam sterilizers by design have a built-in ‘overkill’ safety margin which can’t be changed by the user, and isn’t counted as part of the end user variable sterilization exposure time — so in reality both manufacturers are recommending the same duration of exposure, just expressed differently. If this slight variation were truly an extended exposure time rather than a difference in expressing a parameter, it would be greater than five minutes.”

Loaner trays

Czarnowski explains how loaner trays cause the greatest problems for his department when it comes to IFU access and use, stating:

“Our regular vendors are now accustomed to providing us with IFUs for new trays, but when a new rep walks through the door, it takes some effort to secure the instructions we need to perform our job with patient safety in mind. We do not have the time to validate all of the instruments that are brought in by vendor reps, and there are times when I do feel concern that the paper I am reading does not reference the product number of the instrument in my hand.”

So what should we do?

“The real problem is that millions of instruments are being sterilized every day and with the vast majority of them, no one really knows if they are clean,” said Schneiter.

Standardize

Ralph J. Basile, Vice President, Healthmark, is a member of three industry workgroups and committees related to the validation of manufacturer IFUs. One is an ISO workgroup that is currently working to update ISO 17664, Sterilization of medical devices — Information to be provided by the manufacturer for the processing of resterilizable medical devices. Another is the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) Sterilization Workgroup 12, which has been tasked with updating AAMI TIR12, a support document to ISO 17664.

Basile notes how there is real change happening in the industry, stating:

“On average, the IFUs that have come out in the past three or four years are far more detailed than those that came out 10 years ago. I personally know of a number of very large, very significant device manufacturers that are going back and updating their IFUs, and in many cases revalidating their instructions.”

Basile explains how AAMI Sterilization Workgroup 12 has been tasked with developing a series of standardized cleaning programs for manufacturers that would serve as a common basis for IFUs. So a manufacturer would select the standard program that would be most effective in getting its device clean and build its IFU around that.

“The big issue today is each device manufacturer is going out and validating their own IFUs so healthcare facilities with thousands of devices have thousands of different instructions for processing them,” said Basile. “There are devices that are very similar to each other in the marketplace but with very different IFUs — and the CS/SPD can’t realistically process those devices two different ways because they have thousands of other devices to reprocess. We are trying to narrow the funnel so that the range of reprocessing instructions and variability are reduced, making it easier for healthcare facilities to comply.”

Visualize

With regards to visualization of bioburden and biofilm, CS/SPD professionals need technologies to see what is hidden from the human eye. AAMI ST 79 states:

“The use of methods that are able to measure organic residues that are not detectable using visual inspection should be considered in facility cleaning policy and procedures.”

“Every single workstation should have a lighted magnifying glass — that’s where to start,” said Spry. “Next the CS/SPD should invest in a boroscope or flexible cameras that can be used to look down lumens. When the FDA raised issues around retained bioburden in arthroscopic shavers a few years back, the agency recommended that facilities consider using a boroscope but I really wish they had mandated it. I’ll go to seminars and ask who uses an endoscopic camera and only a few people will raise their hands.”

But as the International Association of Healthcare Central Service Materiel Management (IAHCSMM) points out in its CRCST Self-Study Lesson Plan, Understanding Biofilm, “Even with the use of most visual enhancing tools, microorganisms will still not be seen.”3 Therefore, “other tests have been developed to help verify that cleaning quality standards have been attained.” These include protein tests and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) bioluminescence tests, both of which test for residual soils and which might also be suggestive of biofilm formation.

“There are products that test beyond what you can see visually and are particularly helpful for lumens and other devices that are difficult or impossible to visually inspect,” said Basile. “For example, we have reagent tests that test for protein and hemoglobin, and another 3-in-1 test for lumen devices that tests for blood, protein and carbohydrate all at the same time.”

Collaborate

The effective cleaning of complex reusable devices is an industry wide challenge that requires an industry wide solution. CS/SPD professionals need to collaborate with all parties who contribute to and are impacted by this issue, including manufacturers, clinicians, purchasing, infection control and risk management.

Schneiter urges those responsible for CS/SPDs in healthcare facilities to “do their homework” when it comes to the devices they are reprocessing, stating:

“If you are the person responsible for the SPD then you have to start asking every reusable device manufacturer for a copy of their cleaning IFUs,” said Schneiter. “Then, determine whether or not they did in fact ‘validate’ the cleaning side, as opposed to providing non-validated cleaning IFUs. When you have two different suppliers of the same instrument — one that has validated its cleaning IFUs and one that hasn’t — you have a moral, legal and ethical obligation to go with the one that has been validated. To gain support from the C-Suite, the SPD has to point out that while it is not a revenue generator, it is a risk minimization department. Truly SPD has as much impact on sterility in the OR as does the surgical team. Without validated cleaning IFUs from their instrument suppliers, they don’t have the ability to ensure that everything they send back to the OR is clean, sterile and moisture free.”

If a CS/SPD professional experiences a challenge when cleaning a device based on a manufacturer’s IFU, Spry urges them to first contact the manufacturer and if that doesn’t solve the issue then report it to the FDA through the agency’s MedWatch gateway.

“Recent incidents have made users much more aware of the importance of IFUs and the need to speak up and talk to their manufacturers to tell them what they need,” said Spry. “It might be as simple as having the right brush that is the right size for cleaning a lumen.”

Basile notes the importance of CS/SPD and operating room (OR) collaboration when it comes to effective device cleaning, explaining how when organic soil is left to dry on a device it makes it much more difficult to clean.

“One of the things facilities can do is make sure devices are pretreated and handled in such a way that drying is delayed and the sooner they can begin reprocessing the better — that’s something everybody can do to improve reprocessing and make it easier to get the device clean but it still doesn’t happen in many places.”

Czarnowski and his team have worked hard to establish a good relationship with their hospital’s OR staff. Through mutual respect and open collaboration, they are able to effectively address concerns related to cleaning of complex or older devices.

“When a doctor wants to use an older device with an inadequate IFU, we track down the manufacturer and request clarification on the company’s letterhead,” said Czarnowski. “At times, we will suggest to our OR Resource team that an alternative instrument should be found, one with a specific IFU to aid us in reprocessing the instrument. There has been some friction but generally our larger establishment will support us in talking to a doctor and asking them to find an alternative device with a good IFU.”

When the OR wants to introduce a new surgical instrument that might be challenging to reprocess, Ricupito says the healthcare organization should conduct a detailed risk assessment to uncover the total cost of ownership for this device. He recently completed development of a protocol for risk assessment of IFUs where the recommended process steps present significant challenges for compliance.

“The first stop in risk assessment is to go to the vendor and gather as much valid scientific information as possible — not from the sales rep or marketing contact but from the scientific and engineering developers of the device,” said Ricupito. “If the IFU represents a challenge there could be unforeseen and costly expectations, such as additional staff or technology resources required to effectively reprocess it. Then bring that information to a quorum of stakeholders within your organization that includes risk management so you can collaboratively decide the best approach and then move in that direction.”

References:

1. Reprocessing Medical Devices in Health Care Settings: Validation Methods and Labeling, Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff, March 17, 2015, http://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm253010.pdf

2. https://www.ecri.org/Resources/Whitepapers_and_reports/Haz17.pdf

3. https://www.iahcsmm.org/images/Lesson_Plans/CRCST/CRCST133.pdf

About the Author

Kara Nadeau

Senior Contributing Editor

Kara Nadeau is Sterile Processing Editor for Healthcare Purchasing News.