In the fast-paced, demanding and often under-resourced central sterile/sterile processing department (CS/SPD) environment, it can be extremely challenging to ensure process quality and the delivery of effective, safe and sterilized instruments and devices to clinical care areas. This article explores the spectrum of quality/sterility assurance best practices – from the easiest and most expedient to implement to the most difficult but highly valuable – and presents some new products and service offerings designed to help enhance the quality and safety of CS/SPD operations.

IFUs and Industry Standards

Manufacturer instructions for use (IFU) and industry standards are there to guide CS/SPD professionals at each stage of the process.

Ryan Lewis, MD, MHA, MPH, Senior Director Medical Affairs and Medical Safety at ASP, explains how, for hydrogen peroxide sterilization, a combination of validation testing documented in IFUs and routine monitoring to verify quality/sterility assurance are generally part of a quality assurance program.1 He references the American National Standards Institute (ANSI)/Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) ST58:2013 (R) 2018, “Chemical sterilization and high-level disinfection in health care facilities.”

“Best practices strive to achieve the highest standard of care,” said Lewis.

Jeremy Yarwood, PhD Microbiology, Immunology & Molecular Pathology, Vice President of R&D at ASP, references AAMI ST58 section 9.5, which recommends a combination of parametric monitoring, chemical indicators and biological indicators/process challenge devices.

“This combination provides the most complete picture for process monitoring of sterilizers,” said Yarwood. “Of these monitors, a process challenge device (PCD) provides the best indication of sterility assurance by providing a challenge greater than or equal to the most difficult items routinely processed (AAMI ST58, section 9.5.4.1). As such, we reference the AAMI ST58, section 9.5.4.3 recommendation to use a PCD at least daily, but preferably in every sterilization cycle.”1

Focus on the people

When asked for best practices related to quality/sterility assurance in the CS/SPD, many of those interviewed for this article cited factors related to the CS/SPD professionals themselves, including the need for executive-level recognition and training, and the team’s ability to communicate and collaborate with other healthcare organization stakeholders.

Barbara Ann Harmer, MHA, BSN, RN, Vice President of Clinical Services, Innovative Sterilization Technologies (IST), describes how a CS/SPD staff member becomes a best performer in his or her department:

“From a best practice model, personnel who work in a CS/SPD should be oriented to their department’s policies/procedures and processes,” said Harmer. “Each staff member should be competent to perform the tasks that he/she is asked to carry out. Competency can be observed and witnessed in many different ways but one of the best methods to use is unannounced direct observation. Inservicing should be ongoing with staff having the ability to review the material and then ask questions after they have had an opportunity to digest the material. And lastly, the performance evaluation is used as a tool to assist with recognizing achievements and areas for improvement while setting future goals and targets.”

Supervisor engagement

“The most value-added quality assurance best practice I recommend is both the easiest and the hardest – supervisor engagement in employee performance,” said John Kimsey, National Director, Professional Services, STERIS. “We readily use the term ‘Leadership Routines’ to describe the routine tasks and activities an SPD leader should do on a regular basis to ensure quality products and services are being delivered. Creating ‘Supervisor Routines’ that allow them the time to observe their staff and work processes, ensure compliance to standard work, and identify opportunities for improvement can make a tremendous impact on quality. Supervisors must be actively engaged on the floor. This is simultaneously easy and hard. Easy because it doesn’t cost anything and only requires the supervisor to become involved and hard because it requires time and the potential for confrontation.”

Relationship building

“Of the best practices I employ number one is building relationships,” said Andrea M. Harris, B.A., CSPDT, Central Service Manager for AdventHealth Apopka and Winter Garden. “I consider building relationships as a best practice because when you have a good relationship with your vendors, the operating room (OR), the environmental services (EVS) team, knowledgeable members of the industry, etc., it makes it easier to get things done the correct way.”

“With our vendors, expectations are stated at the door,” Harris explained. “Our OR team usually coordinates the delivery of vendor trays, but they know to request instructions for use (IFU) from the vendors if we have not previously processed the tray. Our department must be kept clean; therefore, building a relationship with EVS is important, so that our work environment begins in the state we need it to be in. Finally, we build relationships with others in the industry. Networking is one of the best practices that one can have. This allows you to have a group of people who can help you identify better practices and how to improve your processes that are currently in place.”

Personal technology

“It is well established that mobile devices harbor dangerous pathogens, including multidrug-resistant microbes,” said Andrew McCarthy, President of Seal Shield. “It is therefore critical for the professionals who work in the CS/SPD to follow the CDC’s recommendation to disinfect their mobile devices at least daily, and to clean those devices at least five times between disinfections. The constant handling of mobile devices - the typical cellphone user touches their device more than 2,500 times daily - means that they can serve as a primary vehicle for the spread of nosocomial infections. UV-C disinfection, accomplished through devices like the ElectroClave, is an easy way to disinfect mobile devices in seconds without the utilization of harsh cleaners, which damage those devices over time. Regular cleanings are thereafter best performed using a microfiber cloth.”

Processes and workflow

At each stage of the sterile processing workflow, CS/SPD professionals have the opportunity to improve quality, whether it is through adherence to manufacturer IFUs, process automation and/or standardization, enhanced product selection, or monitoring, testing and validation of their equipment and work.

A holistic approach

According to Joseph Hannibal, Marketing Director for Sterilization, Surgical and Infection Prevention, Halyard, a holistic approach to sterile processing is an effective way to not only improve quality but also boost efficiency.

“Given that space is often a factor for sterile processing departments, an ideal solution maintains sterility while saving on space and creating a more efficient workflow,” said Hannibal. “Therefore, it’s best for SPD professionals to think about the sterilization process holistically and consider a vendor whose solution addresses packaging, storage and transportation. A holistic system can decrease the number of touch points, which is always beneficial for sterility maintenance. If your facility uses a sterilization wrap for packaging, make sure to choose one that is designed to easily identify breaches. Also, consider a solution that allows you to store your wrapped trays without stacking and enables easy transport to and from ORs.”

Cleaning is critical

“An instrument can be clean without being sterile, but it can’t be sterile without being clean,” said Marc Esquenet, Vice President of Ruhof Corporation. “This statement supports the fact that cleaning is the most critical step in the reprocessing cycle and should precede all disinfection and sterilization processes. Failure to do so can inhibit microbial inactivation and compromise the disinfection or sterilization process. Improperly cleaned surgical instruments and complex reusable devices, such as endoscopes, place patients at serious risk of healthcare acquired infections.”

Detergent considerations

He explains how enzymatic detergents designed specifically for cleaning reusable medical devices have been proven to improve performance over non-enzymatic detergents for cleaning soiled devices, therefore, choosing an enzymatic detergent that conforms to the new 2019 ASTM:D8179 Standard Guide For Characterizing Detergents For The Cleaning Of Clinically-Used Medical Devices guideline can assure positive results.

“According to the guideline, detergents are made up of a collection of cleaning agents with no one component exclusively responsible for its performance,” said Esquenet. “There are appropriate test methods to determine if a detergent has all of the required components. The tests set out to determine rinseability, biodegradability, cleaning efficacy, material compatibility and toxicity.”

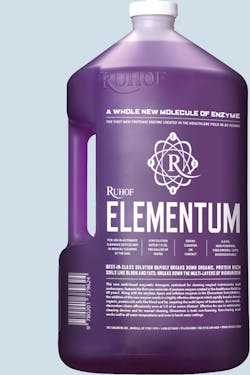

Esquenet points to Ruhof’s new enzymatic detergent, ELEMENTUM, as an example of advanced product innovation that conforms to ASTM:D8179. He says the product consists of the first new protease enzyme created in the healthcare field in 40 years.

“Passing all of the required tests, Elementum consists of powerful dispersing agents, tough solubilizing agents, advanced builders, four enzymes and produces astonishing results,” said Esquenet. “At an extremely low dilution rate, 1/8th oz per gallon, this best-in-class solution rapidly breaks down organic, protein rich soils and breaks down the multi layers of bioburden.”

Don Rotter, Lead Technical Account Specialist, Ecolab Healthcare, notes how automated cleaning processes are superior to manual cleaning because they minimize variation. He states:

“Adequate cleaning of devices being the prerequisite to successful sterilization means sterile processing departments must eliminate variation in cleaning processes. Automated washers and ultrasonics provide less variation compared to manual cleaning processes, yet this equipment is still susceptible to component failure and its function challenged by human factors.”

Tray assembly

Tray assembly is another area at risk for quality failures in the CS/SPD. According to Braun C. Kiess, Director of Sales/Chief Financial Officer, RST Automation, the quality of surgical instrument tray assembly is often affected by the absence of a uniform structured assembly process.

“Missing instruments, inadequate inspection and technician distraction when they need to leave their workstations once or multiple times to hunt for missing instruments are all factors which affect set quality,” said Kiess. “Inaccurate instrument counts are another qualitative factor which results from technicians checking off count sheets in instrument management systems from memory because it is too time consuming to check them off one at a time.”

RST Automation has created an Assisted Instrument Management (AIM) suite of vision technology products, which utilize a structured process that helps overcome the weaknesses of current tray assembly methods.

Monitoring, testing and validation

Another quality/sterility assurance best practice is the monitoring of processes, testing and validation of successful results, particularly related to sterilization.

“As the adage goes, you can’t manage what you don’t measure,” said Erin Manning, Vice President Marketing, Verrix. “When it comes to sterility assurance, monitoring is important not only for compliance but also for problem solving and process improvement. The more frequently a process is monitored, the more tightly it can be controlled. Monitoring every sterilization load the same way ensures consistency in the standard of care provided to all patients and minimizes risk in the event that a sterilization failure occurs. Frequent monitoring empowers sterile processing professionals with the valuable data they need to make informed decisions and help protect patient safety.”

David Jagrosse, CHL CRCST and consultant to oneSOURCE, recommends the use of ELM to enhance quality and patient safety. Jagrosse references AAMI ST79 2017, which guides users to perform biological indicator testing, specifically section 13.5.3.2, which states that users should monitor (test) “at least weekly but preferably everyday and with loads containing implants.”2

“It does not prohibit users from going above the recommendation,” said Jagrosse. “I highly recommend increasing the frequency of biological indicator testing through every load monitoring (ELM). A financial and ethical case can be made to do so.”

“A deficiency in automated cleaning processes detected promptly through daily testing is ideal over delayed discovery through testing less frequently,” said Rotter. “Sterile processing staff not only need to understand how to use commercially available indicators as intended by the manufacturer, but correct interpretation, documentation and storage of the results are also imperative for quality control purposes.”

Jagrosse points out how AAMI gives guidance (13.7.5.1 section C) on how to handle a recall when sterilization failures occur.3

“It tells us that when there is a failure we are to recall all goods to the last known negative BI test,” said Jagrosse. “This can mean hundreds of items and potentially dozens of patients - I refer to this as a ‘window of liability.’ To eliminate or close this window of liability, facilities can practice ELM with biological tests. From an ethical standpoint, why should some patients have biological testing done on their instruments and some not? What would you want for your loved ones or yourself? ELM provides the safest patient care possible while ensuring an equal continuum of care.”

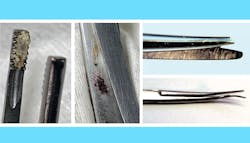

According to Esquenet, visual verification following cleaning is a great way to examine results, as noted in ANSI/AAMI ST91: Comprehensive guide to flexible and semi-rigid endoscope processing in healthcare facilities: “Careful visual inspection should be conducted to detect the presence of any residual soil.”4

The Ruhof Corporation’s Visual Inspection Borescope (VIB) allows for instant visual detection of internal debris and damage inside the channels of an endoscope, reducing the risk of device related infections. The Ruhof VIB’s advanced visual inspection system includes a state-of-the-art camera system and intuitive software providing high resolution, knowledge-based images to help quickly determine the condition of medical devices and instruments.

It all comes down to patient safety

“When we talk about quality and sterility assurance, we are really talking about patient safety and the impact CS/SPD has on the ultimate quality measurement; surgical site infections (SSI),” said Gregg Agoston, MBA, VP Minimally Invasive Surgical Support, SpecialtyCare.

Agoston explains how the CS/SPD directly affects patients’ risk of SSI in two ways, as defined by American College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society’s Surgical Site Infection Guidelines: Operative time and sterilization of surgical equipment.2 The CS/SPD can extend operative times if instruments are not available or functional, and can impact patient safety if instruments are not properly cleaned and sterilized or high-level disinfected (per the manufacturer’s IFU).

“Unfortunately these goals are often not met as there is a silent epidemic of non-sterile and/or non-functional instruments that make their way to the OR every day across the country,” said Agoston. “If it were not for antibiotics and other steps to minimize SSI, we would likely see this epidemic in the news daily. The reality is that our population is aging and more people will require surgery, bacteria are becoming more virulent and time to antibiotic resistance now is being measured in weeks and months versus years. This equates to a perfect storm that could result in many more SSI and patient deaths from them. For these reasons, CS/SPD must do all it can to meet its goals of instrument availability, functionality and safety for every patient.”

CS/SPD Specialization

References

1. ANSI/AAMI ST58:2013 (R2018), Chemical Sterilization And High-Level Disinfection In Health Care Facilities, September 2018

2. American College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society: “Surgical Site Infection Guidelines, 2016 Update,” January 2017, Volume 224, Issue 1, Pages 59-74

3. ANSI/AAMI ST79:2017, Comprehensive guide to steam sterilization and sterility assurance in health care facilities, November 2017

4. ANSI/AAMI ST91: Comprehensive guide to flexible and semi-rigid endoscope processing in health care facilities, April 2015

About the Author

Kara Nadeau

Senior Contributing Editor

Kara Nadeau is Sterile Processing Editor for Healthcare Purchasing News.